'Capitalism delivers the goods'

tracing out ineluctability and the emergence of global one dimensionality, via two idiosyncratic Hegelian scholars, Fukuyama and Marcuse

The ultimate ‘destination’ of this post is the shipping container, and the process of containerisation, and how it might have always been about containment.

This follows on from the sad present I sketched in stacksistence, a making do with all that is left of the ebbing dreams of the past half century.

To get there though, first, I have to deal with globalisation’s meaning, and two Hegelians: first Fukuyama, then Marcuse. This is the work of this post. To prepare the reader, the first bit is a kind of reflection on the lost atmosphere of a cultural moment; the second bit, which is rougher and more theoretical, ‘drills down’ into some postwar moments when Marcuse managed to spy what was, at that time, still early in its gripping unfolding.

This is still something I am definitely still thinking through, and share with you as it is in formation.

I’m now exhausted having written it; typos I’ll fix in the morning. Enjoy.

~

I grew up in an age and milieu that held lots of promise, and held up lots of promises. By the late 90s, there was even a globalisation guru called David Held, who did seem to hold up globalisation as the heroic (heldenisch?) process of processes: however bad the present world could be in its particulars (underdevelopment), it was going to be big-good in aggregate (big development). The big-good was coming soon, the god of goods was to be delivered, the big present of a global future was imminent.

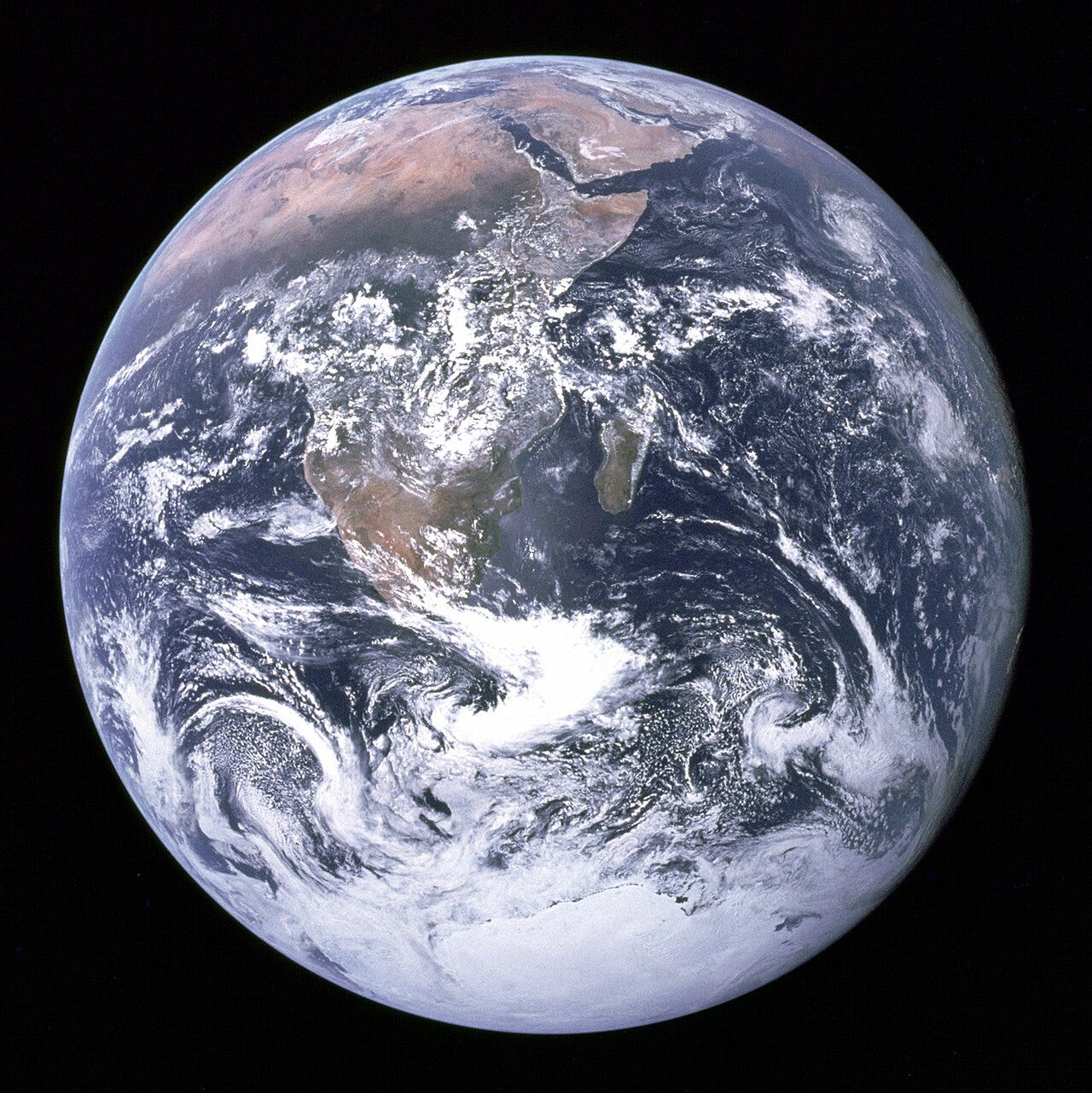

I was at the young end of a generation who were told to go out and meet the delivery of the big-good by living our dreams. We were told we could live our dreams, told we could have it – if we wanted it1. All we had to do was know what we want and then want it, and go out into the lonely planet, with a Lonely Planet, and seek and have it. Between the Blue Marble and the Black-Eyed Peas2, the planet was mirrored back as a space held aside for us, and we were fully allowed hold it – and we too felt held enough to confidently think ‘all of this’ could be within our grasp.

As young Gen Xers, there were a pair of related limits on how we could live our dreams. Firstly, we had to stay cool, living in paradoxical ‘effortless effort’. We had been born in the postwar after the postwar had been won for and by the West, long after The Birth of the Cool (‘in 57 [NB this meant that ‘the cool’ was Boomer II era]). And we were all, though we were not allowed to say it (not aloud!), ‘trapped in the rigor mortis of cool’3 to varying degrees.

Secondly, we had to reach up for our dreams without ever ever trying too hard. This was a very different verticality to that of the Gothic cathedral. It was part of how we all – had to – keep our cool, as individuals, with subcultures. The worst thing you could be was a try hard: the kinds of swatting grinding striver who had to work for it and showed themselves at their limit, cracking a sweat in public, working ‘til their grip got shaky, showing in some cool-crippling way that they were a too hotly desperate for whatever it was, and didn’t and could never dream of holding the world (oh so) effortlessly. The world was not to be grappled with, it was to be held without trying, achieved without being seen to be wanting too much. Losers couldn’t live their dreams, ‘cos they gripped their hopes too tightly, worked them too hard.

One should never show labour; key chains were on show, but supply chains had to be hidden.

From my corner of the world, in my subcultural milieu, the gesture of the era was an effortless kickflip landed by a skater flowing so beautifully it just popped out of them, almost without their having noticed, certainly without their having cared too much4.

The coolest thing would have been someone who could land kickflips and heelflips without ever having had to learn or practice. Inside the 90s ideal of skateboarding, even grinding didn’t grind, and – if you were truly cool – you never fell. And if you fell, you never hurt yourself. And if you fell and hurt yourself, you got straight back on and kept going, and still wouldn’t be seen dead in a helmet.

The master of the era was effortless, and they held the world in a fully formed way, without ever trying too hard.

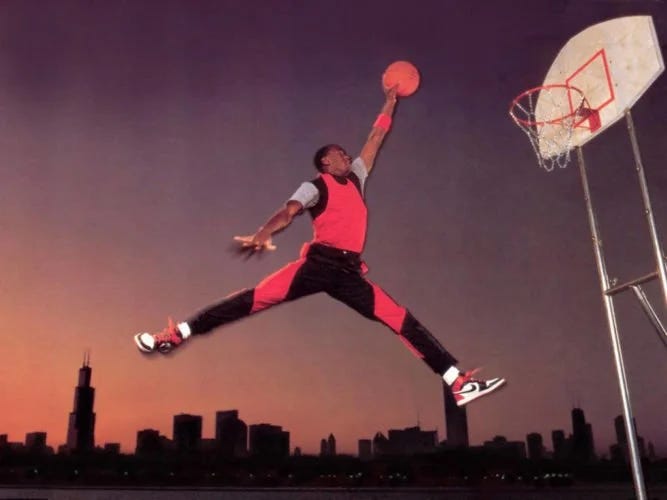

Jumpman conveys the global reach of this ideal embodied in NBA form.

In 1998, nine years late to the party (and I was always arriving at the tail end of a party which was still going, still had some good party left in it), I read the National Interest essay version of Fukuyama’s ‘End of History’. Read and wrote an essay about and hammered Fukuyama. Hammered Fukuyama using Appadurai and some other postcolonial theory, I think. I can’t remember the argument I put forward, because as someone trapped in the ‘effortlessness’ of cool, the ‘argument’ would have been whatever I dreamt up, whatever poured out of me without trying too hard.

What could I have known about ‘89 in ‘98? I didn’t yet understand Hegel, Marx, Leninism, and the fate of the GDR and USSR. Beyond seeing the wall falling footage on TV and being able to feel my way through Scorpion’s ‘Winds of Change’, I had zero grasp of the historical significance of the Cold War. I had zero grasp of the historical significance of historical significance5. Moreover, I would have resisted any effortful attempt at gripping it hard enough grasp it, because that would have meant being a try hard6. To mix the skating and balling metaphors, if a slam dunk essay on Fukuyama happened, it would have just had to pop out of me, ending with a swish. If it did, this just proved I was talented – which no was was allowed to say they were, but everyone dreamed of being (and secretly half thought they were, but were terribly afraid they were not).

Like most similarly formed and framed undergraduates, I recall my allergic reactivity to the trumpeting arrogance of Fukuyama’s America-ness. Even then, I perceived something whiffy in the very notion that history would culminate in “an absolute moment—a moment in which a final, rational form of society and state became victorious”. Even through the darkened Ray Bans7 of my self-enforced arrogance and naivety, I intuited that the post ’89 90s were still some kind of historical era – the era being held up as globalisation, in which we would be held by globalisation if we dreamed and were talented and actualised our talents by living our dreams. In the era of globalisation, ‘we’ travelled where we pleased, landing kickflips in any of the world’s empty corporate concrete areas, effortlessly partaking of the era of Jumpman’s beautifully reached, grasped global victory.

To sum it back at Fukuyama, if the 90s was still some kind of era (full of transients and transitions and contradictions and maybe even dialectical movement), this was ‘somehow’ because it was not about all about America, or even about Americanisation (in the way the world so easily is for a lot of Americans). As Appadurai said, in phrasing which still rings true for Ukranians, Gazans, and so many regions now,

“for the people of Irian Jaya, Indonesianization may be more worrisome than Americanization, as Japanization may be for Koreans, Indianization for Sri Lankans, Vietnamization for the Cambodians, Russianization for the people of Soviet Armenia and the Baltic Republics... one man’s imagined community is another man’s political prison” (Appadurai, Disjuncture and Difference…, 295).

In a world where everyone – including everyone’s culture and group – was still scrambling to colonise everyone’s space, everyone’s territory, everyone’s headspace, while setting up sneaker factories and military bases, it could never (yet) ever be the end of history. Even in the shadow of Sonic Youth and Michael Jordan (and the unstated fact that 90% of my musical-subcultural cues had come from the US throughout high school), my 1998 could never be “the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government” (4).

Fukuyama lead with the triumph of the West as the triumph of the Western idea. This seemed easy enough to knock down, even post ’89, even against the apparent “total exhaustion of viable systematic alternatives to Western liberalism”. That just seemed like something an arrogant American would say, proving the proximity of arrogance and ignorance, the idea that highness and power is the ability to dominate without knowing what you’re talking about or how shit rolls in 97% of the world. I perhaps recognised my own ignorance and arrogance in the other here.

And yet: what was harder to argue against was the notion of ineluctability that Fukuyama followed with:

“But this phenomenon extends beyond high politics and it can be seen also in the ineluctable spread of consumerist Western culture in such diverse contexts as the peasants' markets and color television sets now omnipresent throughout China, the cooperative restaurants and clothing stores opened in the past year in Moscow, the Beethoven piped into Japanese department stores, and the rock music enjoyed alike in Prague, Rangoon, and Tehran” (essay).

Für Elise in Isetan Shinjuku, Motley Crue cassettes on tables in Rangoon, or even Western ‘culture’. It don’t quite nail the triumph that Fukuyama was tapping toward: didn’t quite then, and really doesn’t now. Actually, the deep insight I noticed then and notice now in the examples listed in the above quote – in spite of where Fukuyama was pushing and pulling it – was just the ineluctability of consumption, in all its brute force simplicity. ‘The universalisation of the final form’ (whatever that form would look like, and however universally universal it would be) was the universalisation of the commodity form8. Its ineluctable triumph would be and was demand driven, and would and did happen – inescapably, bottom up – as the market delivered the goods.

So Fukuyama but glanced his own insight9, driving his ideas-heavy Cadillac at overconfident speed, Las Vegas to Washington as all the world, without a back glance in the rear view mirror.

It just clipped me on the way past, but I kept thinking about it. I was left with this glancing blow of ineluctability, and it stayed with me.

~

Only a year later, in ’99, Naomi Klein dropped No Logo. Like a lot of people of my generation fumbling their way through their 90s, this really dropped a formative seed bomb in my thinking. The supply chain of ineluctability was suddenly visible – and we even knew something was wrong with Nike, and the fact that the Nike swoosh was then, she wrote, the most popular tattoo. This world, globalisation’s world, was a fucked up world, a world of exploitation. Oh…

In what remains of this post, I want to dwell on ineluctibility and think it back to one of its key moments of articulation, because I think it is really important. Ineluctability (in the absence of knowing where it came from, and why it’s here, and what it wants from us, and how we’re implicated in it) contributes to a deep and abiding sense of powerless and heteronomy many of us experience in subtle and profound ways every day.

Where did it (the process, the feeling) come from? What caused it? Who saw it first, and how can we get out of it, if we wish to.

Ineluctability was not something that that Fukuyama noticed first, even if he noticed it, in ’89. It was just something that I first noticed, in ’98, in Fukuyama. I just grazed the surface of it, as appropriate to a decade of grazes and surfaces.

In the ambit of this mode ineluctability is a postwar thought, one that was articulated –directly and fully formed – by Marcuse in 1955.

~

‘Capitalism delivers the goods10’.

This is the phrase we have been living under for the past several decades; this is the ineluctability we all live under (with, by), scramble for, ‘get rich, or die trying’ to master.

At a collective-planetary level, we have been clinched by our desire to live the dream of the affluent society through the globalisation of consumption. It was not a matter of living our dreams, but rather, buying their sign value in commodity form, and having it delivered to us – usually so we could store it in our garage, add it to our sets, make it part of our system of objects in the system of objects.

But this is not just an ‘end user experience’. This is because the ineluctability of the affluent society was clinched by the primacy of distribution, rather than production (its industrial-labouring enabler), or consumption (its drive, our investment, our lack). And the primacy of distribution (next post, and back here), was secured at planetary level by containerised shipping, consolidating around the time of the Blue Marble.

Seeing the primacy of distibution is crucial because distribution is morally agnostic, a purporting and porting of pure technicity. Distribution pervades our collective-planetary life as an instrumentarian power that works through the establishment, expansion, operationalisation, and entrenchment of technical zones. This means that, as consumption has spread, so too has an extensive, expansive securitized technicity that has effortlessly repelled any visibility as political, as domination, for seven decades.

The prophecy of ineluctability is spoken in a language of technical operations11, it cannot be seen as an immoral agent, as stoppable, as a regression.

As global logistics, the pervasion of distribution looks like progress, looks like what is necessary, looks like the fulfilment of needs – and indeed, it also really is this, based on the need for fulfilment we live by in the fulfilment society, a need we are utterly dependent on and cannot escape, oppose, can barely imagine otherwise.

Marcuse’s insistence that ‘capitalism delivers the goods’ speaks to something much deeper than neoliberalism, or even the domination of the digital as surveillance capitalism, and it cuts across all cultures, in all their distinctness, and is operative anywhere in the world, and expanding, everywhere in the world.

This means that, even if we wanted to (and do we?), it has tapped in much deeper, and is harder to root out or replace (and we do not have a replacement for it, and [arguably], we do not wish to replace it). In 2024, anywhere outside the logistical system is a warzone and hellscape12 where, for good reason, people would do anything to clamber aboard, get in, get their piece of the logistical pie. In relation to distribution, there are those striving to get rich, and those struggling as they die trying. So of course we plump for our only comfort; the alternative is banishment and exposure to death13.

So then: ‘capitalism delivers the goods’ – in its becoming as the fulfilment society – is the actuality of planetary ineluctability. This is what I wish I could have seen, what I wished I could have written back at Fukuyama about his ’89, from the position of my ’98.

And in theory, I could have done, for we have been capable of knowing this to be our fate and domination since ’55, when Marcuse told us – so directly – this the one dimension we end up ‘in’, as part of our becoming one dimensional14. And yet we still fail to know it; and yet it is seldom discussed –or even recognised – in 2024. Why do we continue to fail to know something we have already known for seventy years, or been capable of ‘already knowing’? Riddle me that. I am obsessed with this question.

There is a widespread belief (in academia, certainly) that somehow ‘we need more data’ to know we are fucked; at some point we may know, but not yet. Never mind climate change denial; we have been actively ignoring what we already ‘knew’ seventy years ago. How are we so capable of not knowing and facing things, things which are everywhere, things which we have also been told, in a fully articulated way, by influential thinkers? Again, this question truly animates my wonder.

Marcuse re-underlined the fundamental point in all his major works of the mid 1960s, in steering his argument toward containment (of which: next post).

“In the affluent society, the authorities are hardly forced to justify their dominion. They deliver the goods”, (xi-xii, 66).

I would actually say that this is more true now than it was in Marcuse’s 60s or Fukuyama’s 90s. In a sense, then, the triumph of the end of history was actually the triumph of one dimensionality by ‘89. We just couldn’t see it in the 90s (cos ‘we’ thought it was about liberal democracy, and because our thinking was shallow and lazy, because we were living our dreams and trying to be cool) or in the 00s (cos we thought it was about Al Qaeda) or in the 2010s (cos we thought its contradictions could be fixed with smartphones).

The global spread of one dimensionality can be seen by glancing at what is the tacit social contract and sine qua non of contemporary life – under regimes and in places as distinct and diverse as India, China, Europe and the US now. Provided Xi, or Modi, or Trump/Biden can deliver the goods, provided they can keep distribution trucking, they can probably remain in power. Elections can be bought, supressed, forgotten or forgone; opponents can be shushed up or disappeared; but one had better deliver the goods.

In fact, it is perhaps only the absence of distribution – nothing at all to do with Western culture or liberal democracy, as Fukuyama trumpeted – that decides which autocracy stands and whether democracy falls. As we live in an era fundamentally characterised by the unspoken, undiscussed domination of distribution, so distribution, in all its apparent technicity, has Fukuyama’s ‘high politics’ by its ascended, frightened balls.

One dimensionality is the current end of our history, this is an end in ‘our’ globalisation history (the history of my generation and its foolish ‘dreams’), is the ineluctable circulation in which we have ended up, and which we are still ramping up, undeterred by ecological catastrophe, societal involution, and rampant alienation.

This was not the fulfilment of what I thought was being promised by globalisation’s boosters. I was out living my dreams, looking for the droids I was looking for. Now I have outlived my dreams’ dreamability. Global one dimensionality is not how I thought I would be held by the future in the future. But it is the fulfilment of what globalisation always was, in fact.

Containerisation, which delivered capitalism’s goods, has also entrenched a debilitating containment of human freedom and a viable collective future.

This really, really raised the question of ‘wanting’ in my generation… you could have what ever you wanted, provided you wanted it…. which meant knewing what you want, which meant (I recall) so many people paralysed by pondering what they really wanted, and not really knowing. As a horizon (and as a different subjective paralysis) this is so different to the sofa king reality of stacksistence, is it not?

The smash hit ear worm stupidity of ‘I gotta feeling’ is the vibe I’m going for: go out and get smashed, ‘cos you got a feeling – that tonight’s gonna be a good night.

Thank you Kodwo Eshun for that one, in his very very 90s book (maybe it’s the most 90s thing imaginable, alongside The Face magazine?), More Brilliant than the Sun

Surely Sonic Youth’s 100% film clip (directed by Spike Jonze, how could it not be?) captures this gesture set in *this* subcultural range of cool. The skaters landing the flips are often not filmed landing the flips (cos landing the flips was so fucking hard and required so much effort and practice!), and are *all* white boys here (in an era that didn't see its whiteness). The older millennial 00s riposte to this clip might be Lupe Fiasco’s Kick, Push.

By that measure, I was living in Debord’s spectacle.. which, in a sense, was true (but a very low pressure, quaint version of it, compared to the world now for so many people. From Comments on Society of the Spectacle: “History’s domain was the memorable, the totality of events whose consequences would be lastingly apparent. And thus, inseparably, history was knowledge that should endure and aid in understanding, at least in part, what was to come: ‘an everlasting possession’, according to Thucydides. In this way, history was the measure of genuine novelty. It is in the interests of those who sell novelty at any price to eradicate the means of measuring it. When social significance is attributed only to what is immediate, and to what will be immediate immediately afterwards, always replacing another, identical immediacy, it can be seen that the uses of media guarantee a kind of eternity of noisy insignificance” (15).

I hope you can see how crippling this introjected constraint on gesture and effort was for my generation: each gen has its baggage, this is some the most limitingly annoying for mine.

Bausch and Lomb ones, moreover, *American* Ray Bans with glass lenses; pre the sell out to Luxottica.

So then, a story of a few Hegelians: Fukuyama, Marcuse… and Marx of course.

Apparently the book does get quite into consumption – I have yet to go back and read it. Like most, I just read and reacted to the essay version.

I’m distilling this phrase, which emerges fully formed in One Dimensional Man (1964: xliv, 46, 82, 87) as a kind of refrain, from passages like the following, already brewing up in Eros and Civilisation (1955): “Still, the guilt is there; it seems to be a quality of the whole rather than of the individuals - collective guilt, the affliction of an institutional system which wastes and arrests the material and human resources at its disposal. The extent of these resources can be defined by the level of fulfilled human freedom attainable through truly rational use of the productive capacity. If this standard is applied, it appears that, in the centers of industrial civilization, man is kept in a state of impoverishment, both cultural and physical. Most of the cliches with which sociology describes the process of dehumanization in present day mass culture are correct; but they seem to be slanted in the wrong direction. What is retrogressive is not mechanization and standardization but their containment, not the universal co-ordination but its concealment under spurious liberties, choices, and individualities. The high standard of living in the domain of the great corporations is restrictive in a concrete sociological sense: the goods and services that the individuals buy control their needs and petrify their faculties. In exchange for the commodities that enrich their life, the individuals sell not only their labor but also their free time. The better living is offset by the all-pervasive control over living. People dwell in apartment concentrations - and have private automobiles with which they can no longer escape into a different world. They have huge refrigerators filled with frozen foods. They have dozens of newspapers and magazines that espouse the same ideals. They have innumerable choices, innumerable gadgets which are all of the same sort and keep them occupied and divert their attention from the real issue - which is the awareness that they could both work less and determine their own needs and satisfactions" (Marcuse, Eros and Civilisation, 1955, 99-100)

This is where Mezzadra and Neilson land in The Politics of Operations, but as often, they use a lot of words, insist their theoretical vocabulary adds something and must be used, and don’t quite say what it is as clearly as might be. They seem to have good theoretical intuitions for pointing at problems, but are less talented at ‘languaging’ them in a way that’s clear and makes any difference to what we already know – or what Marcuse was saying sixty years ago.

unless there is wilderness; but is there wilderness?

And, to wit: even if there were wilderness, we, as groups, are almost unable live in it – we would be shot and burned out, replaced with plantations.

It’s a whole separate post, but in short, what Marcuse means by one dimensionality is the rule of the technicity of operationalism, and the loss of any ability to imagine, think and express other possible dimensions of existence (including those of artistic, erotic and political emancipation), leaving us trapped in our air-conditioned trap, doing data entry into our laptops, waiting for our wellness package to be delivered… the following phrases, which gather up and distil a lot of what was worked out in Eros…, flesh this out: “The Happy Consciousness – the belief that the real is rational and that the system delivers the goods – reflects the new conformism which is a facet of technological rationality translated into social behavior. It is new because it is rational to an unprecedented degree. It sustains a society which has reduced and in its most advanced areas eliminated – the more primitive irrationality of the preceding stages, which prolongs and improves life more regularly than before. The war of annihilation has not yet occurred; the Nazi extermination camps have been abolished. The Happy Consciousness repels the connection. Torture has been reintroduced as a normal affair, but in a colonial war which takes place at the margin of the civilized world. And there it is practiced with good conscience for war is war. And this war, too, is at the margin – it ravages only the "underdeveloped" countries. Otherwise, peace reigns. The power over man which this society has acquired is daily absolved by its efficacy and productiveness. If it assimilates everything it touches, if it absorbs the opposition, if it plays with the contradiction, it demonstrates its cultural superiority. And in the same way the destruction of resources and the proliferation of waste demonstrate its opulence and the "high levels of well-being"; "the Community is too well off to care! (77-8).