‘Give us this day our daily spurts’/Rude Goldberg Machines (fantasy is no coincidence, part three of three)

or: how to ‘build a giant waste-producing Rube Goldberg machine as a global economy that gives us dopamine spurts every day’, by aligning the phone fantasy of control w that of the sovereign consumer

So then, fantasy is no coincidence.

What is this producing, at scale, in the global supply chain?

Let’s bring this into sharp focus.

I was listening to two podcasts recently where people – thinking through its discontents really and rarely thinking about these materialities of our world, the world I shorthand via Gorzworld and VaporSpace – carefully described the global supply chain as a Rube Goldberg* machine.

For those who don’t know, Rube Goldberg was an American cartoonist famous for constructing contraptions as complicated as they could possibly be, and still (improbably) function. As Wiki reminds me, those of you who are English might think of Heath Robinson (G Images search for Rube Goldberg or Heath Robinson to get the flavour). If you’re Japanese, think also of chindogu; if you grew up with Milton Bradley in the 80s, think of Mouse Trap… then scale it planetary…

These imaginative evocations funnel us to the point: every time we grab our control wands to diddle the lack out of ourselves or drill it back in, we are connecting to a whole global supply chain from which we are compelling information, energy, and materials (see Weiner for the postwar distinctions between those things, and read Vogl, Smil and Helen Thompson to get a sense of how energy and pipelines are *not* the same as information, which is not the same as communication &c).

We might feel alone in our fantasy; but actually, we are compelling the behaviour of the whole world every time we enact our drilling and filling with our control wand.

Whatever floats our boat

a ship will bring our way.

In one ‘cast episode, which is really worth a listen, Christopher Mims summarises what he found looking right across manufacturing, shipping, trucking, fulfilment, and sortation, after a decade covering technology for the Atlantic and WSJ. Can I just ask you to notice: this is so basic to how we actually live, yet it is such a rare perspective… consider, by way of contrast, how much ‘journalistic’ attention was sunk into Depp/Heard, or the King’s coronation… how much time do you spend on your phone, or just masturbating about your fantasies… (or preparing to do so, buy scrolling for new toys) and how little time do you think about supply chains? Fantasy is no coincidence…

In this interview, what Mims underscores is how the global supply chain is like a Rube Goldberg machine whose key characteristic in the early 2020s, coming out of covid is that it is – so improbably – still functional. ‘Somehow it works’, although it is tight as a drum (to the point of making me go hmm), and incredibly vulnerable to breakdown from any kind of extrinsic shock (or polycrisis combo thereof).

Covid, the key shock we all (differentially, unevenly) lived1 through when he was researching the book, actually just nudged consumption a few % points here and there. As mentioned, Peter Hessler's excellent feature examines the supply interplay of markets and feedbacks between China and the US during this time, and how the pandemic has made the US even more dependent on Chinese manufacturing. That’s all it took to stuff everything for a couple of years at least; and it nearly killed civil aviation. We forget most of this, just as easily as we forget that covid has killed anywhere between 7-21 million people, and continues to circulate and mutate.

But what if we consider that covid was just a moist run from the Wuhan wet market?

Think about the Rube Goldberg bringing all the wigs and dildos2, all the Lacks and drills and No More Gaps, then consider what human-to-human bird or swine flu will do... or a bungled escalation around Taiwan... or the implosion of Japan’s economy and/or the US banking system... or a bad AI that gets out and fucks with the energy grid and cloud servers. Any of these events just mentioned are non-trivial possibilities that may/not come down the pipes in the next few years. What would that do to the Rube Goldberg machine?

Polycrisis indicates, moreover, that ‘any and all of the above’ could co-emerge and interact in all kinds of nonlinear and ‘bad surprising’ ways: one might look at Lebanon, Sri Lanka, or Pakistan right now, already, today, to see what this does to everyday life. These are not just hypotheticals, these are already the lived realities of hundreds of millions of people today.

And as a disruption to global supply chains, we are dealing with a shock to open systems at planetary scale, which would affect everyone uevenly, as well as having all kinds of further – compounding – nonlinear, uncontrollable ‘bad surprising’ effects. Well, what then? This would be a sudden and unpleasant change for anyone used to flicking and clicking to have stuff delivered. We need to consider the larger community of unpreppers alongside the preppers. We roll our eyes at the latter, maybe; but we don’t consider ourselves enough as woefully under skilled, unaware, and under-functioning because the global supply chain is over-functioning for us, because this aligns with the business and operating models and profitability of Amazon and its manufacturers.

As I’ve been mentioning, it’s really worth listening to what Mims is trying to convey about the global supply chain from the US side, both in light of the rare synoptic perspective his research generates, and because it is such a vast sink hole of consumption for all the manufactured stuff that China and Vietnam can sink into it.

And for all of us, complexly implicated in this global supply train (as well as the whole Amazon and Uber Eats paradigm of ‘almost anything… ding dong!’), it’s really worth reading his book, especially alongside MacGillis’ Fulfilment. It’s easy to descry America as ‘broken’. What’s more interesting to look closer at the evidence and stoies Mims and MacGillis offer us, then notice is the paradoxical truth of just how broken the US is, yet how (improbably) well the global supply chain also still works... for now...

In a second ‘cast I wholeheartedly commend to you, Simon Michaux engages with Nate Hagens (and see their earlier appearances together on Great Simplification, they’re all good) to generate some genuine, proactive, interdisciplinary thinking around the ‘break glass’ ideas and practices we’ll need to have ready-to-go, if/when the current supply chain does break down.

Michaux talks about the Old School, the Vikings, the Realists, and the Arcadians3, self-identifying as a kind of Arcadian boyscout (which somehow fits with his version of Australian-ness, with which I’m very culturally very familiar4). In unpacking what we might have to do when we can’t get rare earth minerals for our phones anymore, Michaux at one point echoes Mims, when he says the following:

‘We’ve just really built this giant waste-producing Rube Goldberg machine as a global economy that gives us dopamine spurts every day. It is totally nonsensical from a resource, energy, environmental standpoint’.

Coincidence notwithstanding, I think this adds in the ecological perspective that’s been missing (thus far) from the space of fantasy and desire I’ve been trying to traverse in these three posts: because alongside control, there’s also the cornucopian fantasy of endless arrival, a forevernevermore of happy endings belied by the many ecological, material and mineral-energy resource constraints are hitting – or have already overshot – as I type.

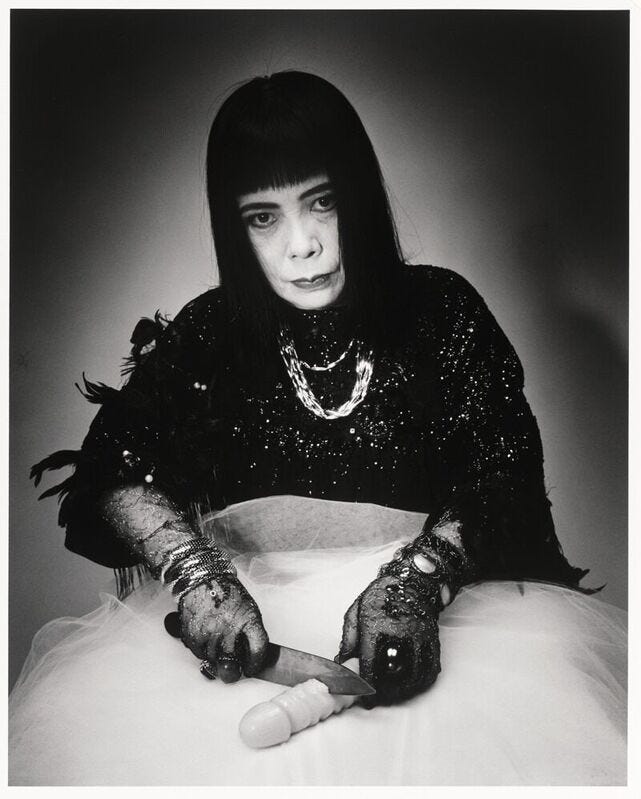

Well then, if we take what I’m suggesting as true – our fantasies are no coincidence – what, aside from control, are the subjective and psychosocial fantasies from which we are getting our daily spurts from this great big Rube Goldberg machine, and how might we connect this from its co-production of waste and nonsense? The ‘pic above intimates this… so now it’s time to talk about Kris and Kendall and Uber Eats.

~

One of the prevalent shared fantasies of Anglocapitalism now is the fantasy of the sovereign consumer. In this fantasy, any of us can behave like a mad Caesar or Princess Borderline, to the extent we are exchanging our money for a commodity or service being brought to us by someone trying to earn a wage.

As soon as we have insufficient funds, this fantasy evaporates, and it’s we who are out there in the rain, turned from a Deliveree prince/ss back into a Deliveroo frog/toad.

I’ve already talked about this by way of the servile service economy of Gorzworld, its two ‘subjects’ – Deliveroo and Deliveree – its tendency to build a utopia of ‘gain without labour’ (for the Deliveree) off the back of precarious exploitation (of the Deliveroo), and its elaboration of an almost endless set of niche products and services (chimp shampooing and monkey tennis, delivered in <24 hours) that do not add any durable socio-cultural value or enhance productivity in any way. It’s a world that allows us to like pina coladas without getting caught in the rain.

Above all, it’s this fantasy-world that triggers the Rube Goldberg from a billion phones each day. This activating connection aligns information, fuels, and materials in favour of the sovereign consumer (and Bezos’ bottom line) by allowing us to command the relentless effort of the world without demanding much of anything of ourselves, and/or without us having nearly anything demanded of us.

For those of us whose coping and defence mechanisms already skew toward avoidance – whether of demand, conflict, or effort – the 2010s and even 2020-1 lockdown were rare and precious gifts: we can be rude slobs, we may not have brushed our teeth, changed our undies, or washed our undercarriage; we may be wearing a filthy oodie and even Crocs. But when the Deliveroo arrives, as Deliveree, even if we’re greasy balls deep in Goblin mode, we can behave like a petty sovereign, and everything in the supply chain must be responsive to this. Goblin King Goblin King…

Until we have insufficient funds.

Jobs and phones are, thus, the key mediators of this fantasy, their co-enabling condition.

A percentage of people enact this fantasy as a way of coping with their jobs, work beyond subsistence to perpetuate this fantasy, or use this fantasy as the booby prize for having to do their jobs. I feel like we’ve all done this over the last five years… I certainly have.

Analogous to the way that ‘mastery’ is the slave’s fantasy, the Deliveree indulges their whim, in no small measure, because there is no structural impediment to their becoming a Deliveroo. In a society structured ‘toward’ fulfilment, provided we have sufficient funds, we can ‘choose’ to compel labour to have things brought to us, rather than be compelled to bring things to another master.

With the example of Uber, I’ve already questioned whether a decade of this style of disruption has got us any societal value add: I think it’s deeply questionable5. Maybe. I think it would be much harder to deny the affordances Google offers by way of search, Maps, or YouTube, the remorseless reliable efficiency of Amazon, the quality and stability of OSX and iOS, or the general net societal benefit of podcasting. It’s hard for me to really see how anyone needs anything Uber has offered so far... it’s worth reflecting on this in our lives. Like 95% of the stuff on sale at K Mart: do we really need it? Do we really want it? Is it actually any good? Most of it is a piece of crap.

However, the extension of this Uber paradigm – kind of an Amazonisation of Uber – takes this to a place that puts paid to the whole she-bang, and is really nothing more, nothing other, and nothing but a global economy set up as and perpetuating a giant waste-producing Rube Goldberg that gives us dopamine spurts every day, and which is totally nonsensical from a resource, energy, environmental standpoint. We are now doing with the Rube Goldberg machine what the rapey-snuffy corners of DFW’s ’98 Vegas trip were doing with porno. To be clear, I’m getting normative: I just don’t think this is even a demographic or need set that should be serviced in anyway. What do I mean by this?

The Jenners are the sublime avatars of this society and its relations; if they didn’t exist, it would be almost necessary to invent them. Please watch this ad and consider what’s going on here.

Here, we have Kendall Jenner, playing the role of petulant, bored teenage princess to a tea. She is so bored, she can’t even be bothered to roll her eyes or cut a cucumber with a sharp knife; she is so bored, by the end of the ad she has produced a huge pile of food waste that it is clear neither she nor her ‘mom’ is going to eat. Her labour is so useless and unskilled that this is clearly the punchline here: ha ha, look, Kendall is unfit for life, yet she lives like a princess.

To her right, Kris Jenner, playing the role of compulsive consumer mom and stupidity triumphant. Oh, the stupidity of it all. Kendall isn’t even that interested in what’s on offer, but Kris just keeps clicking – ‘I’m on Uber Eats, wan’ anything?’ – and the bag arrives. Ding dong!

Bags of what? For this campaign, ‘whad’ever’. Actually, it’s vegetables, fresh vegetables that arrive with a person-less

ding dong,

only to be presented, poorly cut, on the bench at the end of the ad (quite obviously this won’t even be eaten by the crew and is going straight in the bin). Kendall is so bored, and Kris is so stupid, and neither of them actually even want or have any use for the vegetables (they can’t even cut them, not even with sharp knives…) yet due to the way the Rube Goldberg aligns the fantasy of the sovereign controller, Kris’ need for tiny spurts of dopamine, her ability to get them through her phone and the ding dong, and the ability of the platform mediating this to control the mobility of other humans who sit lower in the global birth lottery than them to get their ‘almost anything’, the most complex feat of human organisation yet deployed, the Rube Goldberg machine itself, stays lubed and primed to be receptive to ‘whatever’ Kris’ control wand keeps commanding and demanding.

In the final analysis, what’s interesting here is how the fantasy of control (and its wand) and the fantasy of the sovereign consumer (on her throne, in her kitchen) is overdetermined by ‘whatever’: global capitalism, for now, for its upper middle and up, can compel labour to bring almost any object to our door through the Rube Goldberg machine. In the background, Depeche Mode’s ‘I Just Can’t Get Enough’ plays; it’s playful, it’s funny – how stupid it all is.

But to push this a little further: is the fantasy now not the push beyond erotic fantasy back into libidinal indifference? No one is really getting off here, no one is getting filled… there’s just landfill after ding dong. And moreover, is this not also an ad that demands preparedness of the supply chain on behalf of a set of consumers who are so so disorganised, unprepared, and helpless?

Uber Eats is now here to service the unpreppers, in a sense. And this is no longer niche: Coles, one of the two supermarket chains in the Coke-Pepsi style duopoly in Australia, has just announced that it’s partnering with Uber Eats across 40 stores: “Uber Eats’ goal is to meet customers’ growing desire to get (almost) anything they need delivered on-demand, and this expansion will supercharge the wide variety of groceries available on the app.”

In Australia, Planetary Overshoot Day was Wednesday 23 March. Three weeks later, the above announcement from one half of the supermarket duopoly. We should look back on 2023 in ten or twenty years time: Deliveroos pedalling around in the rain; container ships so big that even the biggest ports need to stretch to accommodate them.... everything around us, destroyed just so we can all play the role of Kween Kris and Kwincess Kendall. Why is this such a popular fantasy? It’s no coincidence that *this* is what we desire. Why?

Luke Heggie’s spot gives us the exit velocity of this, when, moreover, the Deliveree is a total arsehole. I give him the final word here.

I know I’m labouring this one a bit, but in Mims’ Arriving Today, Amazon workers are continually amazed by *just how many* sex toys Americans buy. What must Chinese girls in Shenzhen or Yucheng – nice girls from the country who came to the big smoke in the hope of a better life – think of the US? … hilariously if you speak Japanese, there’s a Chinese town mentioned in the linked article… called Chikan.

I feel like I have to add a category here, based on my current institutional life: there’s a substantial group whose basic relation to the world is parasitical… they treat institutions as a way of extracting resources and career advantage for themselves… they hog the mic and hog resources, aren’t inclined to share or care… it’s basically all about their own benefit, which is about holiday houses and long haul travel… I’m speaking specifically about a substantial minority of people in positions of high office and leadership in my organisation, especially the set of functionaries who are usually >50, white, middle class and upper, who are earning >200k already, and often like 350k, essentially to govern by having meetings where dashboards and executive summaries are used as a way of withholding ‘scarce’ resources from people lower in the hierarchy than them… Weber would call them nullities… but they do not only annul or spiritually immiserate (in Stiegler’s terms), there’s a wilful blindness and nonrelationality being actively practised here… (which boils down to being told ‘we don’t have enough money!’ by people who earn 6-10x what the *already middle class* people further down in the hierarchy earn, and >10x what the sessionals and students can earn … this class of parasitic functionaries abound in many a large complex organisation these days…

Less Croc Dundee or Steve Irwin, and more like someone between Les Hiddins’ appropriation of deep indigenous knowledge (the Bush Tucker Man) and Mad Max, especially the Max of Mad Max Two….(still great) there’s a whole ‘thing’ about white Australian masculinity here… (the Bush Tucker Woman is an Arrente elder, but we didn’t get a doco series with her in the 90s… ) ‘to be deconstructed…’

In the short term, if it allows people I know to make more than they would doing hospo, and this helps them make rent, maybe that’s okay. And if it allows harried families on a Friday night to get a salty meal on the table without having to prepare food or do washing up, maybe there’s some modest gain in the affordance (but for whom?).