Rifts (part one of three)

How we find ourselves stuck glumping, with no time for reflection, ‘now’ that time is out of joint

This is a very surreal moment in human history, as far as we yet know it. The 2024 Presidential Election is a synecdoche for this ‘hole’ of America – not much to add1.

I’ve tried to pinpoint this zeitgeist as stupid and stubborn in its surreality: a distended ‘between’ times where even the betwixt is indeterminate because the afterward is unsure. In its stubborn thus-ness, 2024 is not so much the end times as the globular glum times. Atom’s Widerstand gives me one auditory imagination of this moment, in its involuting distension.

How can a hole be so full of itself; how can something so little last so long?

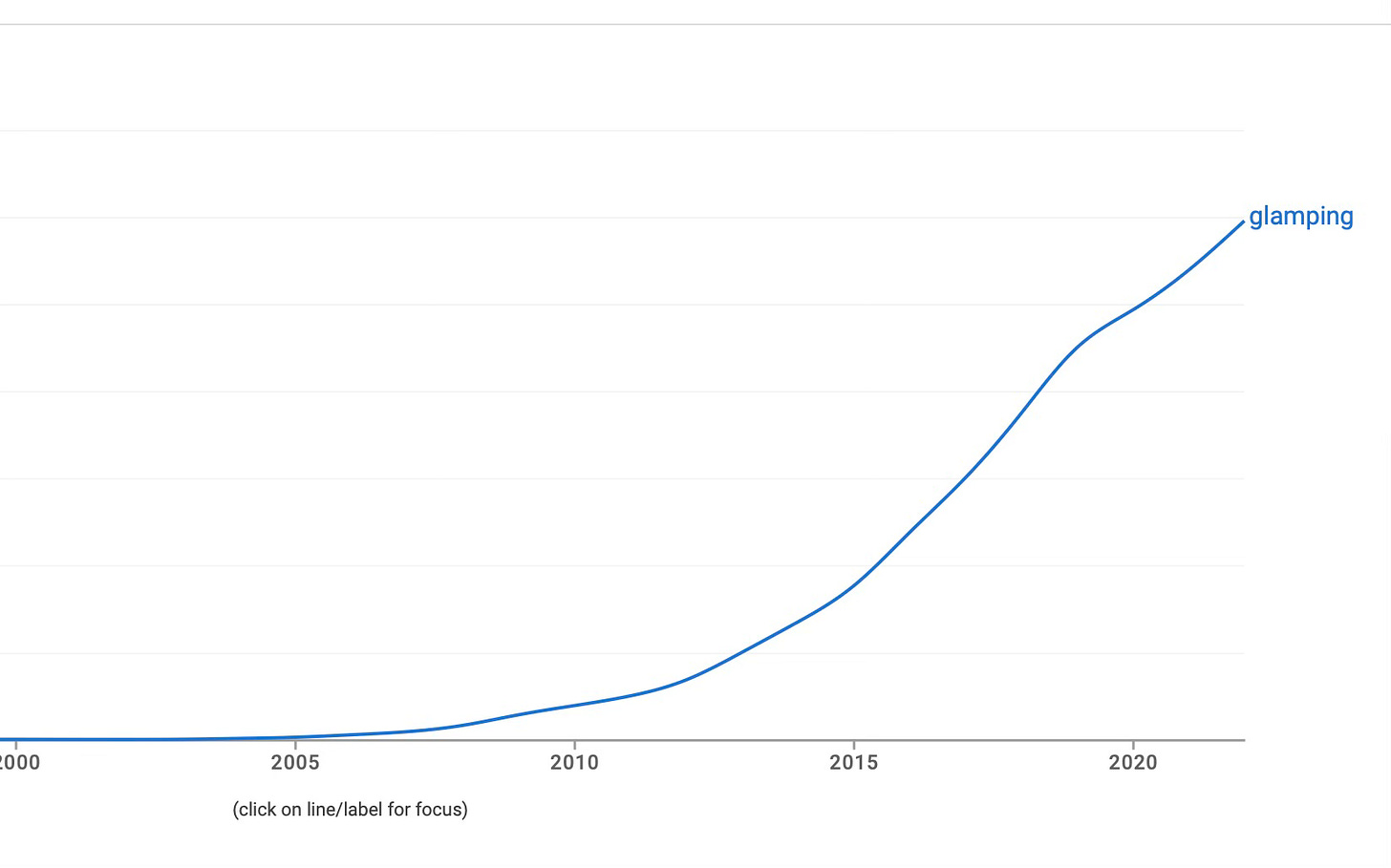

If a signature white ambition of the pre covid 2010s was glamping, then in 2024, we find ourselves in the beige bulge blurging distensions of glumping.

glumping: a user’s guide

What is glumping?

Glumping is disappointing, it takes so long, it doesn’t end; it’s not clear why we came here or what we want, we can’t get or go anywhere; we’d prefer not to stay here, but we’re seeing it through anyway. It’s expensive, it’s poor value – we don’t enjoy it, no one sees the barn – it’s full of single use plastic, it’s bad for climate change: we make video calls encouraging people to join us, saying what fun we’re having.

Behind all the unhappy-crappy campers in our uneven glumping collective, I feel all these rifts. They’re not yawning like we are, and they’re not gaping yet (as we will be), but I sense them. Are they ogling us, these rifts, while we glump in gloomy ruminations? No, the rifts are there, not quite slouching toward Bethlehem, but hovering in the shadows, the way The Groke loiters on the margins of Tove Jansson’s Moomin novels. Reports observe the rift in hard data; Adam Tooze induces the rifts by overlapping concepts into intelligible syntheses (which are getting a bit too China positive for my vibe). I feel the rifts in my bones, and I glimpse their groking grip on our future – if rifts can grip2.

The first rift is at least as old as Hamlet, 1603:

‘time is out of joint. Oh cursed spite, that ever I was born to put it right!’

Four years later, in 1607, the English established what we retroactively know was the first permanent colony in the Americas. Seven years before Jamestown, and three before Elsinore, Elizabeth the First established the East India Company by Royal Charter. Go forth, go break the Dutch. These were fateful years for opening rifts.

Then the rifts got away from us, got away, pulled away, and accelerated.

Hartmut Rosa pegs the true takeoff of social acceleration to the eighteenth century, but we can already spy the geneses of the rifts of modernity in the anteceding six hundred years. In the remainder of this post, I’d just like to peel one these layers by focusing on time, to open the rifts to a few more posts: one on metabolic rifts, one on competitive individualism and anxiety, and a final one on the intergenerational-interpersonal rift I viscerally feel between myself and my students and my children. This was all opened by reading this short piece on Anthropic’s new application of Claude, that can basically operate as a less-than-optimal office worker: in a world were apparently 47% of Medium content is Ai-generated already. I’ll return to this in later posts, but it surely bolts ahead and transforms the meaning of text, writing, reading, and work – in ways we are totally unprepared for.

But first, let’s open the rifts; let’s do some rifting spelunking.

Time is out of joint, 17C: social acceleration via the shift to circulation

In the seventeenth century, social acceleration was induced by the shift toward the primacy of circulation – a rifting shift we are still living through, and which is still accelerating acceleration. As Rosa writes,

“From a historical point of view acceleration driven by the logic of capital valorization began not in the sphere of production but precisely in the spheres of distribution and circulation: as we have already seen, transportation and communication noticeably accelerate from the seventeenth century onward, long before the great technological innovations that led to the acceleration of production processes. One essential reason for this is that in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries capital first accumulated in the area of trade, that is, in the sphere of circulation. This created a pressure to increase the speed of shipping because subsistence economies and guild systems at first prevented a corresponding development in the realm of production. Thus, the acceleration of trade and transport historically precedes the acceleration of production, which first achieved its dramatic highpoint later in the industrial revolution. As a cursory glance at the breathtaking change and massively increased transaction speeds in the financial markets quickly makes clear, the progressive development of the monetary system functioned as a cardinal accelerator here, a development that is not yet finished (Rosa, 163-4)”

Capital has a huge and inherent speed advantage over labour at a mass-collective level, especially where the physical distribution of people-and-things in space is concerned. This is among the (many!) reasons we feel so overwhelmed by the rift opened when circulation started to demand we move more quickly than our bodies can without prostheses3.

This ‘annihilation of space and time’, eventually as a Zoom call at the speed of light over fibre optic cable running along abyssal trench (also full of cat videos and snuff videos, ‘porn and twaddle’), is also the annihilation of quiet space, enough time to recuperate from the days efforts. As capital distributes time faster than we can move through space, the day becomes a set of efforts that is worth a little less every day, faced (as Rosa reminds us) with the ramping ramping of metastability.

It is so curious that, as a species, we invent these huge apparatuses of speed and comfort that burn us out and crash themselves. But this is a big rift, and continues to ravel the planet as it unravels us. A tragicurious winding up that is unwinding us. I say this as someone who nearly fell off a Stairmaster the other day. It’s so easy to do. Climbers beware.

The essence of the rift here is that there is no spacetime for reflection. The ramp keeps ramping, like the glamping curve in the 21C, and we’re left with an accelerated situation, evacuated of reflection. This is captured so well by Virilio:

When a situation is accelerated, one does not reflect. One has a reflex reaction. Acceleration and speed, not only in calculation, but in the assessment and decision of human actions, have caused us to lose what is time proper, the time for conception, the time for reflection. We enter into a feedback loop. Without an interface, either. When we drive faster than one hundred and seventy miles per hour, we are no longer ourselves. We are plugged in. It is no longer a philosophical, reflective activity, but a pure reflex” (150).

time is out of joint, two: from ascetic regulators to the primacy of the machine

A second way in which time was put out of joint was by time itself – by its measurement, by the imposition of clock time – as an interposition between us and world. Lewis Mumford is very attentive to this in Technics and Civilisation. As I covered in an earlier post, reading aloud the key section from T&C, the monastic order of the Benedictines, the Rule of St Benedict, ordered time as an askesis where a group of people, withdrawn from worldly affairs, repeatedly turned their collective attention to the higher task of communing with God in prayer, at intermittencies governed by the Eight Canonical Hours: “Matins or Vigils, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline” (see).

Timekeeping was rulekeeping, which was rulemaking; and for the first time, a community was set into routinising intervals. This was the birth of regularity. The rift that opened here was not the regulating (governing) management of time as time, it was the primacy given to a mechanism, to which we attribute an autonomous being – which rules over all of us. Even after the death of God, time, which was used to know God, can be used to rule us – in his absence. So if ‘time waits for no man’, what we fail to notice is how we’ve attributed a causal agency to a collective abstraction we’ve built from a measurement tool originally conceived for a more specific and transcendent purpose. Now: it’s time to go to work.

God is dead. Back to work.

The implications here are surely riftworthy: long before Weber’s Protestant Ethic made a virtue of abstemious toil, way before Prince Hamlet and Queen Elizabeth in the 1600s, and centuries before the shift toward circulation that Rosa notes, a rift opened between us and our world, one supposed to open us to the world as a regular sequence of moments. As Marx noticed: ‘moments are the elements of profit’.

Mumford is so perceptive here,

“…one is not straining the facts when one suggests that the monasteries – at one time there were 40,000 under the Benedictine ruled – helped to give human enterprise the regular collective beat and rhythm of the machine; for the clock is not merely a means of keeping track of the hours, but of synchronizing the actions of men” (here).

The tragic irony all this points to is clear, and it shows us back to our glumping, the sticky stuckness of something that, paradoxically, has accelerated way, way beyond control.

By synchronising the actions of a group of people who collectively agree to ‘synchronise watches’, we have produced a profound asynchrony between what the body needs and what the clock demands. 24/7 global capitalism is the death of sleep, the death of darkness and long flickering shadows, a grave of the fireflies; it is a bathing in blue light that does not get us clean, it is an immersion that takes us out of our bodies and into our heads – in a way that is fragmenting and disintegrative, yet sticks us into stuckness.

And so we find ourselves glumping: trapped in the airport lounge, with a phone in our hand, waiting for Trump to not/get elected, for our ‘connecting flight’, for a way back to a home which, in an age of collective glumping, can no longer be existential – although the stakes surely are.

Anything that piles here, holes here – there’s a hole in one.

It’s not bad style. Rifts can mix metaphors, because everything pours into them: holding environment as sink hole.

We walk at 6km/h; world-class marathon runners manage 20km/h for a little over two hours; stage coaches managed 8km/h in the 18C and this only doubled to 16km/h with scheduled coaches; bicycles lifted this above 20km/h for ordinary people for the first time, by the late 1880s (when the safety/standard frame replaced the ‘high wheeler’/Penny Farthing).