Tells us about your piles, stacks of books, sets of thoughts, sub- and suprastack

reflections 'beyond stacking', on where my head and heart's at with this work, given the 2023 media ecology

This morning an interesting thing happened: I strongly noticed a desire not to post or write. Once I tuned in to that, I realised that there were some reflections underneath the grumpy reluctance. So I wrote ‘that’, which is this.

Tell us about your evolving understanding of the approach of the blog, and where your head’s at now with this approach, twenty months later?

When I started this blog in January 2022, there was a kind of self-understanding of a few different things.

First of all – as I reflected nine months ago, in November – there had been a really arduous period of ‘academic labour’ 2020-2: the effort required to do writing of a quality I could be proud of during the pandemic, on top of all my work tasks, all of which entered our lockdown home, along with our three kids, and home schooling for two of ‘em. The enervating work of channelling this writing peer-reviewed journal articles, for career-neoliberal reasons1.

As I concluded at that point (and my view is unchanged)

“By the end of the year last year [Dec ‘21] (with last year being the kind of pandemic year it was at home anyway), I basically concluded that the proper ratio of academic writing could be defined as

‘that which consists in the most amount of labour for the fewest caring readers’”.

With this settled personal truth in mind, the blog had been a way to write ‘fast and loose’, to recover what was intuitively interesting to me.

~

There’s a really interesting double concept in motivational psychology that is apposite here; the distinction between ‘approach motivation’ and ‘avoidance motivation’.

With ‘approach’, you are drawn or driven toward the thing, because you want to, need to, love to.

With ‘avoidance’, beyond the straightforward ‘have to’ of work, what’s interesting to recognise is a set of tasks (and maybe a whole mindset toward life, friendship, sex, you name it) which is fundamentally about what you diligently do because you fear what will happen if you don’t do it2.

It's so interesting to clock that (luckily!) I was fortunate enough to have the early childhood and birth privilege to feel confident pursuing my own autonomy by way of approach motivations, most of which are intrinsic and immanent: they emerge from within, and are their own satisfaction. I am a person who does many of the things they do – because I want to. And I’m lucky enough to be able to, most of the time.

However, it’s also so clear that writing journal articles stemmed from a very, very powerful avoidance motivation: I have been writing – two a year since 2011! – so as not to be buried in teaching-marking load forever, so as not to have my career3 destroyed by a field in which teaching is not accorded the respect, recognition and prospects that cranking out ERA point ‘gold coins’4 is. It’s worth noting whatever tasks occupy this place in your own life, and noticing that these are powerful motivations, and powerfully destructive of mental health.

Let’s chuck a 36kg kettlebell on this: to what extent has ‘work’, for most of us, become an avoidance motivation fest... how many of us are ‘doing things’ because of a fear of penury and worthlessness in a brutally competitive society...? Rushing around, feeling tapped and burned out, pumped and dumped, all so we can ‘keep buying pie and ice cream’, as my daughter noticed this morning. Three year olds know things that adults forget or occlude with the excresences of their self justifications and those of the culture in which they subsist, running scared from the feared axe falling.

In a context such of this, it felt urgent and meaningful for me to get back to the practice of ‘just writing’, letting a lot of things that were not yet and/or not at all conscious ‘speak’ (and see next response), in terms of framing the writing, letting it go in that direction without second guessing, and then just going with the flow, rolling with the punches, mixing the metaphors – at pace. Above all, the idea was to turn up each Tuesday early early, write and write, and hit publish around midday, before I felt like I was ready to let it out.

Twenty months later, I’m checking in and noticing that this approach no longer has the internal urgency that it had.

The ‘release’ of this urge is actually good news. Therapeutically, I think my decision, and what I followed through with, it ‘worked’, I think it served its purpose, it helped me.

This is my feedback to many of you: thinking by writing, especially in ways unlike your ordinary or professional writing practice, if they’re slow, or measured, or are pushed through constipated editorial or bureaucratic processes – and with your name off it, for a while – might be cheaper and better than ‘analysis5; it’s probably not as good as a really excellent psychodynamic therapist could be, but try and find one who’s available – and then afford them.

So I swept the alleys of my mind, got through some pseudo topics that were sitting there in relation to my unfinished business with Frankfurt School critical theory (now finished, thank fuck), pushed some of the way into some sustaining interests I now durably have (Gorz, ecology), and brought me back to some topics of mine that I’d lost self-confidence – and heart – with in the late 2010s (transport systems, logistics, supply chains), due to work trauma and alienation, which I think I’ve largely worked through.

Once this happened, a flood of ideas – actually far too many for any given post, to the extent that I can’t even remember half of what I’ve written here, or which post it was in – emerged, and I think I came out the other end with ‘something like’ what I wish to be preoccupied by for this decade, in my writing.

However: this set of topics now demands its audience; and its audience (rightly!) should now demand something that is clear and tight.

Writing for writers has its place; writing for readers now has its moment, and demands its project.

However: it can’t be peer-reviewed journal articles. I no longer wish to support this cumulative evil of churn and reticulation.

So: the time has come to stop ‘playing jazz’ (writing for myself, for internal reasons); the time has come to tighten the fuck up and write in a measured and edited way for this audience, with my name attached. Whether or not that is on substack, I’m not sure (I’ll come back to this, below).

But to distill it: the process of doing this for twenty months has ‘got me through’ the second half of a really tough and complex internal-mental working through that’s about as old as my daughter, and she’s turning four in October.

Her growth shows me that time rolls faster than thoughts in words, and it’s time to move on, hit publish on something else, because I’m not quite ready.

I would commend this process to you; it has been entirely worthwhile.

What have you noticed about the role of the unconscious – as far as we can know it – in relation to this approach (and writing more generally), and how have other ‘life ecology’ factors impinged on this – and how have these factors ‘expressed themselves’?

Yes, well... back in 2006-8, I was working as a music hack, smashing out words on a Monday morning based on phoners I’d done with artists, producers and DJs I didn’t always care about or care to know about. It was amazing giving oneself over to the rough craft of the music hack, and treating writing as a quantity of words that had to be delivered over by a certain time, in good enough form. There’s truly something to be said for that, both for how it gets past one’s vanity (and attendant writer’s block), and for the chops you cultivate. I really learned how to crank, and (sadly, at times for this blog’s ‘overflow’) this appears to be a skill I learned and can deploy when need be.

...but in relation to the unconscious: are you writing something (for someone) who’s inside you, or outside you? And are you writing from the past or the present?

As Chodorow notices – in a way that’s so lucid it becomes enigmatic again – psychoanalysis can teach us to see more clearly the extent to which we continually confuse internal and external realities (what you are saying/writing, how I am feeling), and how we always mix up past and present. Me/you, now/then…

You’re not my mum; this isn’t something happening in this conversation now... yet/so I’m angry about something that someone (else!) said to me 25 years ago (that I’m still stuck on), a conversation that was not this one, in a place that is not this one, that I’ve externalised in some kind of formative and perhaps cripplingly limiting way.

As Luhmann notices of communication:

most understanding

is a misunderstanding

that has no understanding

of the mis-.

...so who or what is being conveyed, and to whom?

In relation to this blog as a practice of hypnagogic writing, it’s really interesting that, when you let it, writing writes you (cue Escher reference). It doesn’t quite ‘write itself for you’ like a generative algo semi-magically seems to*....and yet, Chat GPT (in French: cat, it farted), like ‘letting writing by writing’, raises anew this same fundamental issue of who or what is writing, and for whom:

who’s the audience and who’s the author, really?

Personally, there’s a set of topics that repeat themselves to me (like a cat, farting), that I have agency with but no control over. They insist and then I make of them what I can. For me they tend to be of a set that’s in the world and in society and the present... in that sense, the world wants to write itself back out through me, based on some idiosyncratic ways I’ve internalised it. When I sit down to write, a whole bunch of shipping containers want to burst out of me.

Containerisation is always about decontainment.

~

...and as I mentioned earlier this year (after giving my students the task of giving GPT a topic, then being critical about and so writing and thinking about GPT’s response to their prompt): AI tends to keep converging back to the same generic, smooth, boilerplate response.

Interpolating Baudrillard by changing a few key words in the following quote (and so making his words my words for ‘you’)

‘All are now rendered sexless in the same hermaphroditic ambience of Chat GPT! All at last digested and turned into the same homogeneous faecal matter (naturally enough, this occurs precisely under the sign of the disappearance of liquid language– too visible a symbol still of the real faecality of real life, and of the economic and social contradictions which once inhabited it). That is all over now. Controlled, lubricated, consumed faecality has passed into words; it seeps everywhere into the indistinctness of things and social relations. Just as the gods of all countries coexisted syncretically in the Roman Pantheon in an immense 'digest', so all the gods – or demons – of consumption have come together in our Super Writing Centre, which is our Pantheon – or Pandaemonium’ (Baudrillard, Consumer Society, 30).

In contrast to Chat GPT’s ‘shit smoothie’ of dead labour6 (a thousand monkeys on a thousand typewriters, the blurst of times), my students’ thoughts and writings all diverged. They were divergent. We are divergent creatures (who write recursive algos that are convergent). To that extent, Montaigne’s meandering essays map to the curvilinearity of all bio-emergent structures – then we ‘cheat’ our tutor by getting Chat GPT to give us a one page summary of Montaigne’s Essays.

Why do we have this demi-urge toward wanting to read convergent writing and smoothed faecality that flows like honey out a shopping mall-sized anus?

Humans now, for some reason, have come to love the geometric linearity of anything that has been shorn and denuded of this forest and river. We ‘love’ the Yarra so much we plonk the Hoddle Grid and Melbourne on top of it; we transform The Amazon into Amazon, we prefer Amazon to The Amazon.

Unboxing is the most popular category of video on YouTube.

In this culture, we prefer to have our writing containerised, so we can consume and discard it.

Writing in the consumer society means involving our selves in something that is about expenditure and waste production, that exists as it accrues privilege and profit to a tiny minority whose position and nous allows them to game it.

...and, yes, this gets at the fundamental problem with writing in 2023: like GPT, I can easily produce more words than most people have time to read, like some biomechanical turk...

Where and how does this land for you, as a ~stack?

Concretely: there were these several other ‘similar’ substacks that I followed to see what people were writing, but I shit you not: I haven’t checked a single post, because I don’t have time.

I’m actually feeling, at heart, that it’s more supra~ than sub~, if you feel me. I feel like this is too much, it’s another excrescence generated by the involutions of publishing; a symptom, not a solution or a salve.

With the limited reading time I have, personally, I wish to read books – bound objects which are linearised (and edited, and polished) precisely so the meanders can be contained and expressed. I’d rather read Montaigne than read people’s suprastacks; that must be true of my own, in this form.

So then, we truly are in the collective grip of The Buribunks7... and the moment I ‘see’ this collective-cumulative effect of all this subbing and stacking, I do not like it, I do not. At a societal level, I’m actively contributing to a problem I dislike, not its solution (which I crave and struggle to see).

...and what about substack itself, both as a platform (with its intrinsic features and quirks), and in relation to the prevalent modes of engaging with text in the culture?

Lol. In a sense the previous spontaneous response answered this already.

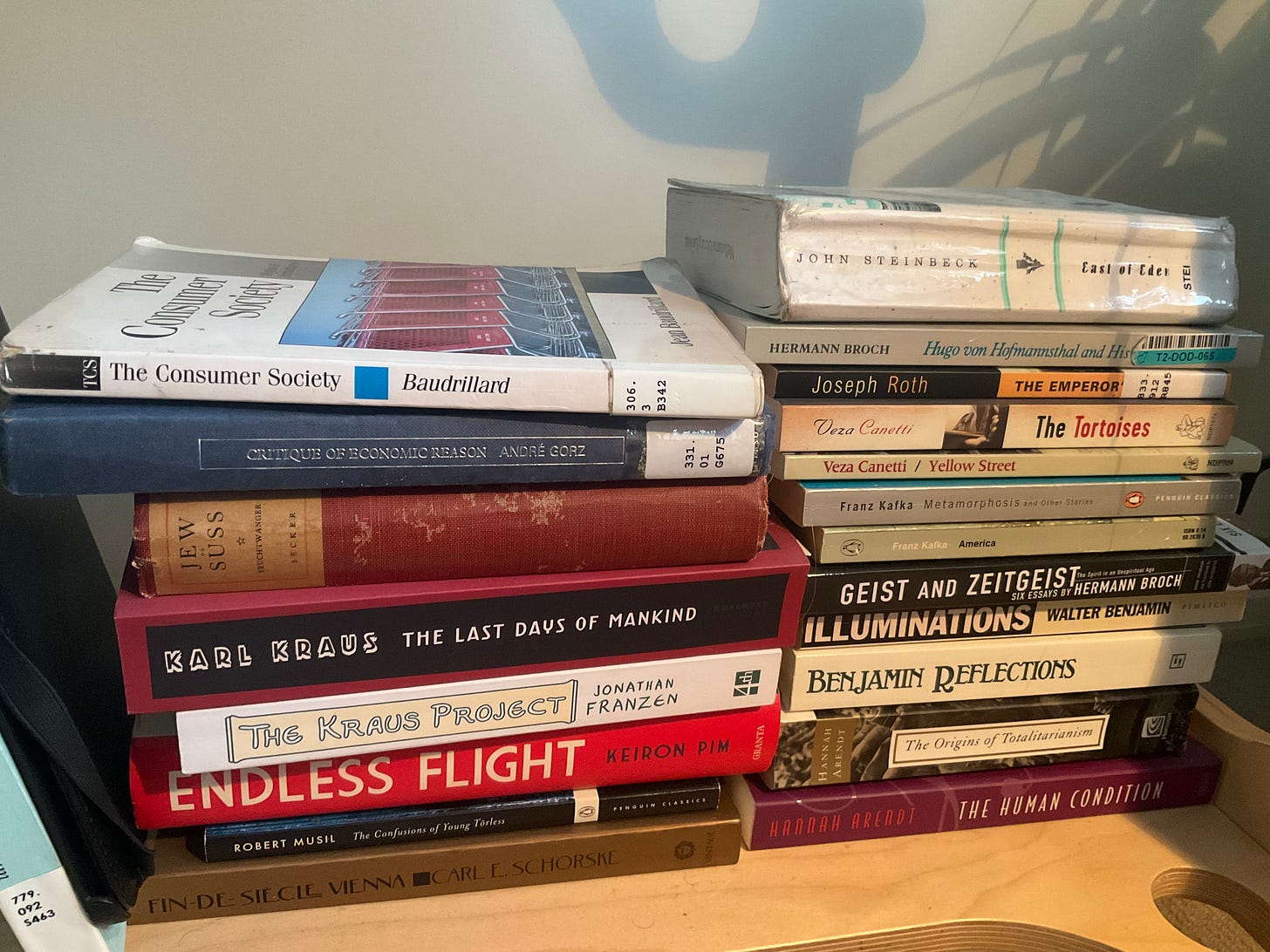

Phenomenologically, I have the same ‘feeling’ when I go into a good bookstore. There are fucking stacks and piles of people’s books. And more than just stacks and profusion, there are packages, collections, ‘boxed sets’, all of which enchain us into further time-consuming consumption. Again, a block quote from Baudrillard, slightly edited, nails it:

Beyond stacking, which is the most rudimentary yet cogent form of abundance, objects are organized in packages or collections. Almost all the shops selling clothing or household appliances offer a range of differentiated objects, evoking, echoing and offsetting one another. The antique dealer's window provides the aristocratic, luxury version of these sets of objects, which evoke not so much a superabundance of substance as a gamut of select and complementary objects presented for the consumer to choose among, but presented also to create in him a psychological chain reaction, as he peruses them, inventories them and grasps them as a total category. Few objects today are offered alone, without a context of objects which 'speaks' them. And this changes the consumer's relation to the object: he no longer relates to a particular object in its specific utility, but to a set of objects in its total signification. Washing machine, refrigerator and dishwasher taken together have a different meaning from the one each has individually as an appliance. The shop-window, the advertisement, the manufacturer and the brand name, which here plays a crucial role, impose a coherent, collective vision, as though they were an almost indissociable totality, a series. This is, then, no longer a sequence of mere objects, but a chain of signifiers, in so far as all of these signify one another reciprocally as part of a more complex super-object, drawing the consumer into a series of more complex motivations. It is evident that objects are never offered for consumption in absolute disorder. They may, in certain cases, imitate disorder the better to seduce, but they are always arranged to mark out directive paths, to orientate the purchasing impulse towards networks of objects in order to captivate that impulse and bring it, in keeping with its own logic, to the highest degree of commitment, to the limits of its economic potential. Clothing, machines and toiletries thus constitute object pathways, which establish inertial constraints in the consumer: he will move logically from one object to another. He will be caught up in a calculus of objects, and this is something quite different from the frenzy of buying and acquisitiveness to which the simple profusion of commodities gives rise (Baudrillard, Consumer Society, 27, italics in original).

As someone who knows writers and editors and has slept with and sleeps beside a former publisher, I know the labour inhering in a book. It takes making! It’s so much work: so many thoughts, so much heart put into something. Yet for most of it, none of us has time to read them, let alone read them well.

Like any inscriptions in a global marketplace of commodities: there are far too many; most will not sell (most of the good ones don’t sell, and then a bunch of craptastically average titles sell like hotcakes); mostly it was a waste of time, a chancey thing, not something where cause and effect, input and output, effort and brilliance ‘in’ and resonance and impact ‘out’ ever get aligned.

Clive James’ The Book of my Enemy Has Been Remaindered' nails this.

...and it’s also interesting: ‘the book’ survived the e-book and The Kindle.... but, in a sense, it hasn’t yet survived itself, or publishing models, in this living environment. This whole ecology, it really impinges on me… I’m quite porous… it’s outside but gets inside me…

~

It’s bizarre that there are still basically two modes of book publishing, trade and academic. The former is ‘kept honest’ by the profit motive and sales – publishers won’t take on a title they don’t believe in and don’t think will sell enough to earn out (or be offset by some other title that will allow it to take a loss – but this so often means that the small, cool, quirky projects don’t get up, don’t get taken on, especially if they’re by authors without a name and a profile, and/or who don’t post hard and have a following on the usual corporate platforms.

Aside from the small (and shrinking) few good university presses, corporate-academic publishing is a total scam: books that won’t/don’t sell are nonetheless taken on8, by ‘editors’ who don’t care what’s in the books or who wrote them; authors get 0 care and support and there’s no meaningful process of structural editing (leaving authors feeling like they and their work doesn’t mean anything, and leaving potential readers with underdone books that are awful to actually read). What comes out are books that no one reads, that don’t sell, or that are on sale for 250 bucks, until no one buys them, then they’re on sale for twenny bucks. I liken it to the sex therapist’s riposte: if you don’t desire sex, is it because you’re not having sex worth desiring? Are these books we’re madly scribbling at, are they worth bringing into our bedrooms, are they worth giving a fuck about?

Platforms like substack are intended to ‘step in’ here as a space between, both for journalists, and for professionals and scholars whose work falls between the cracks of the above two modes for books (and journal articles).

What’s emerged with substack has its own features, affordances and benefits, many of which are worthwhile, most of which are marginal (and the margins are getting slimmer, I think. Not surprisingly however, it also has culturally/capitalist-rooted 1%er dynamics analogous to those of the corporate streaming platforms, where a small number of incredibly popular substacks, all of which are monetised, make out with all the loot and profile, while 99% of people beaver away at The Buribunks (note below).

Personally, the substack posts I’ve actually shared over the past twelve months have contained data and advice that is specific to a genre or topic-based audience (eg, stats related to neurodivergence in children and how it effects X in education). The ones of mine that people have said they appreciate (and thank you), they don’t tend to share (the stats tell me). Thus, style of stacking that fits ‘success’, according to Substack’s model, which is about growth (always be capturing a bigger audience!) and revenue (make your stack into your career!) offer a definite set of enabling constraints one can work with, and/or ignore.

I don’t think there’s a problem with a marginal substack that stays marginal, that has a stable audience of 40-50 people, like this one (just lost one subscriber last week).

I also think there are good reasons to notice and work with the media ecology that exists, and to ‘decide’ to make a substack or LinkedIn (or whatever) work.

Ultimately however, the Biggest Winner in these ecologies are Ed Sheeran, Noah Pinion, and above all, Samantha Ramsdell (the TikTok smash with the world’s biggest mouth) who, as a human paradigm success story, ‘life mouths’ the w/hole consumer society for us, so we can ogle it.

Where then do you want to point your writing; what makes intuitive sense to you now that’s different to twenty months ago?

I’m now putting my heart into writing a book.

And I would like to write essays, although I don’t know if the dynamics are ultimately any different, even if you’ve got what it takes (and what resonates!) an ‘in’ and a network to promote you to the threshold of success.

Peter Hessler’s latest feature was amazing, and shows me how great long form can be…9

...and so: what should we expect, where is this going to head?

I’m not sure. And I’m actually totally okay with that, for a few months.

I would like to continue to post with Baudrillard, come back to Gorz, and finish with Freud and death drive and guilt (maybe not all of Civilisation and Its Discontents now...). But I’m not sure if I have the time and energy for this, before the new thing emerges. I’m hoping to have that for you by November. Let’s see.

It’s also important to bring direct and slightly uncomfortable awareness toward noticing that any given time has past, and that it’s time to move toward the next thing. Ironically, then, the form of blog has taught me when it’s time to wind up the blog in this form over the remainder of this year.

And (to repeat) I need a few months to think about what the appropriate forms need to be.

In the meantime, I’m going to post here if I feel like it; stay with me if you like, but don’t expect 3,000 words in your inbox once a week.

With my lectureship specifically, I ‘should’ be doing about 2.5 papers a year to keep my research allocation (the lowering of which means more teaching/marking, which means fewer opportunities and less time in the long run, means ‘being buried forever’). I am no longer given the time it takes (according to comparable measures at ‘nearby’ institutions’) to do this: as with many things in post-covid austerity unis, the University is squeezing the milk cows whose labour it purchased, in order to do budget repair, because the ‘loot’ from the 2010s was not saved for the ‘rainy day’ of the pandemic, but rather spent on salaries/super, consultancies, marketing, and shiny new buildings. They want more, they give less in return, then demand that it be done in the ‘less time’, ‘or else’ there’s the threat of even more chores (which, spiralling, take even more time away from the writing and thinking).

Usually here there is an ‘external’ authority whose actual role is as the avatar of an internalised authority… some kind of big Other you’ve introjected… usually something parental, Führer-y, Big Brother-ish, Tiger Mother-y (you know what yours is).

The really important thing to notice here is the internalisation of the norms of this thing called ‘career’.

For those outside academia: for each article that is published, we get a ‘point’. At different bureaucratic levels in any given institution’s hierarchy, one needs to get ‘more points’, such that a lecturer will need two a year, every year, while a full professor will need five (where five points = a book or X $ in research income). It is this, not knowledge, that drives all of academic publishing. We really need to digest the implications. It’s not about knowledge, it’s about a fear of failure, marginalisation and rejection by a hierarchical bureaucracy; and the ‘winner’ is the person capable of cranking the most points, year after year, for thirty years (regardless of whether what they write is actually adding to the sum total of knowledge). It would be very interesting to see if Foucault would have thrived here.

While I was doing psychoanalysis I was also sending long voice message ‘soliloquies’ to a friend of mine, and she would send them back. They would be ten or fifteen minutes long; I knew that she would listen carefully. This was of greater value than analysis, actually, and didn’t take as long or cost as much. This is really worth noticing: mostly what people really crave is to speak without being interrupted, and to be listened to very carefully. The difficulty is that many people just ‘talk at’ and won’t/can’t come to the point, or talk around it… and most people don’t/can’t/won’t fucking listen. A good psychoanalyst is a human-sized ear with the timing of a great stand up comedian.

Cos, after all, it’s just scraping and trolling the Internet for its inscriptions, all of which ‘we’ collectively wrote ‘for it’, for free, as academic labour (paid for by tax payers) or as the ‘theft’ of what professional writers wrote and write.

Carl Schmitt’s satire of a future in which we became society of beings who consistently wrote and disseminated their personal diaries; more here.

to sell to university libraries, who pay a premium/too much… having said this, fewer of the unis are buying the hardbacks the system really needs to stay stable… electronic deliveries subprime the whole thing, and now, if we need resources, they’re usually paywalled behind janky interfaces… so much for the dissemination of knowledge for the greater good.

but it takes a market the size of the US to create an elite niche for The New Yorker, who don’t actually pay their writers that well, and are tricky to work for, by reputation. It’s all cultural and symbolic capital, hey…. BUT: Hessler, like Alec MacGillis, and The Author’s Voice and the Fiction Podcast… at its best, it’s so much better than most of the dross out there.