Hello all,

I’ve been working on a bigger post here, which I think should be out next week. What I’ve been trying to do is think through the point at which the integrated spectacle of pure simulation we live online spirals into an increasingly precarious materiality. How can I square the circle with Jia Tolentino’s profession of Broken Brain, the moral abyss of what is escalating in Gaza now, and a world in which climate catastrophe, driven by mass-ive material processes unfolding as extraction, circulation, construction, destruction, is percolating away there in the attentional background? These connections truly matter; I’m not yet convinced we’re making them well enough.

Baudrillard is typically a thinker we would only use to help us with Jia’s conundrum. In the foreground, it’s very clear to see that he bet the house on simulation and burnt his bridges with Lefebvre’s Marxism, Bourdieu’s sociology, and the poststructuralism of Foucault and Deleuze & Guattari (which have dominated most of left-critical scholarly work since… is there a Verso or Duke book that isn’t kinda one of those?) Baudrillard *seems* like he capitulated into a kind of Neitzschean nihilist, spouting aphorisms in aviators in the Arizona desert, like a character from 90s DeLillo. However, reading him carefully and in order, not only are his criticisms of his fellow travellers of Paris’ 5th arrondisement valid, I think there’s something we can take from his untimely disclosure of our almost total domination by the metaverse back to our catastrophically bad geopolitics and our fragile and damaged ecology. The following is a DFW-size footnote from Symbolic Exchange and Death, which I quote in full, because there’s something in it about capital we haven’t yet quite seen (or obscene?). Once I start talking about Minecraft next week, this should become clearer.

Basically, where it seems like Baudrillard traded his 5th Arrondisement ‘cow’ for the magic beans of simulation, it is actually we who have traded reality – for broken brains, for broken cities, and for broken ecologies. And it’s only once we start truly seeing how captivated we are by what we are held captive in, that we can break out of that.

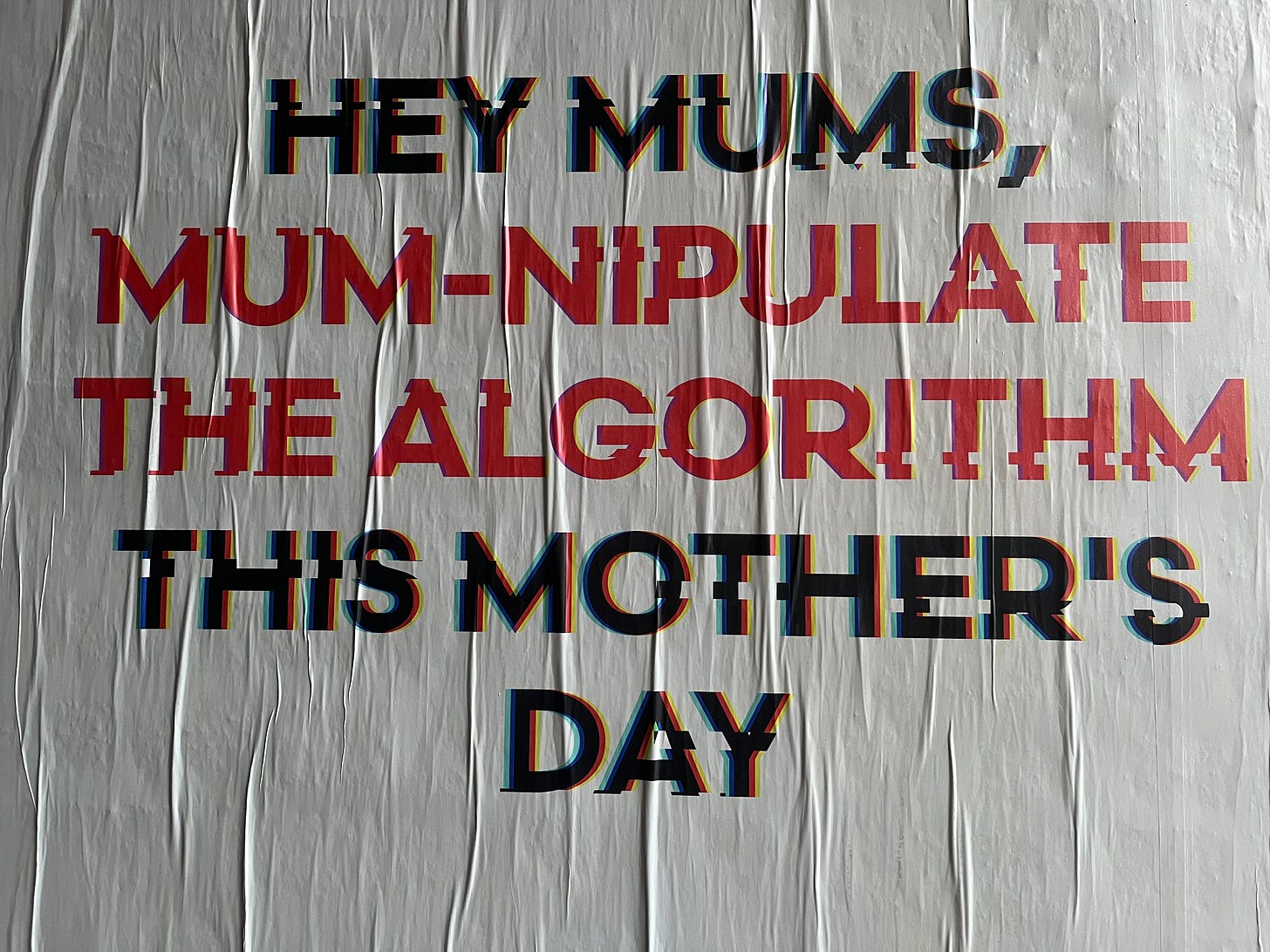

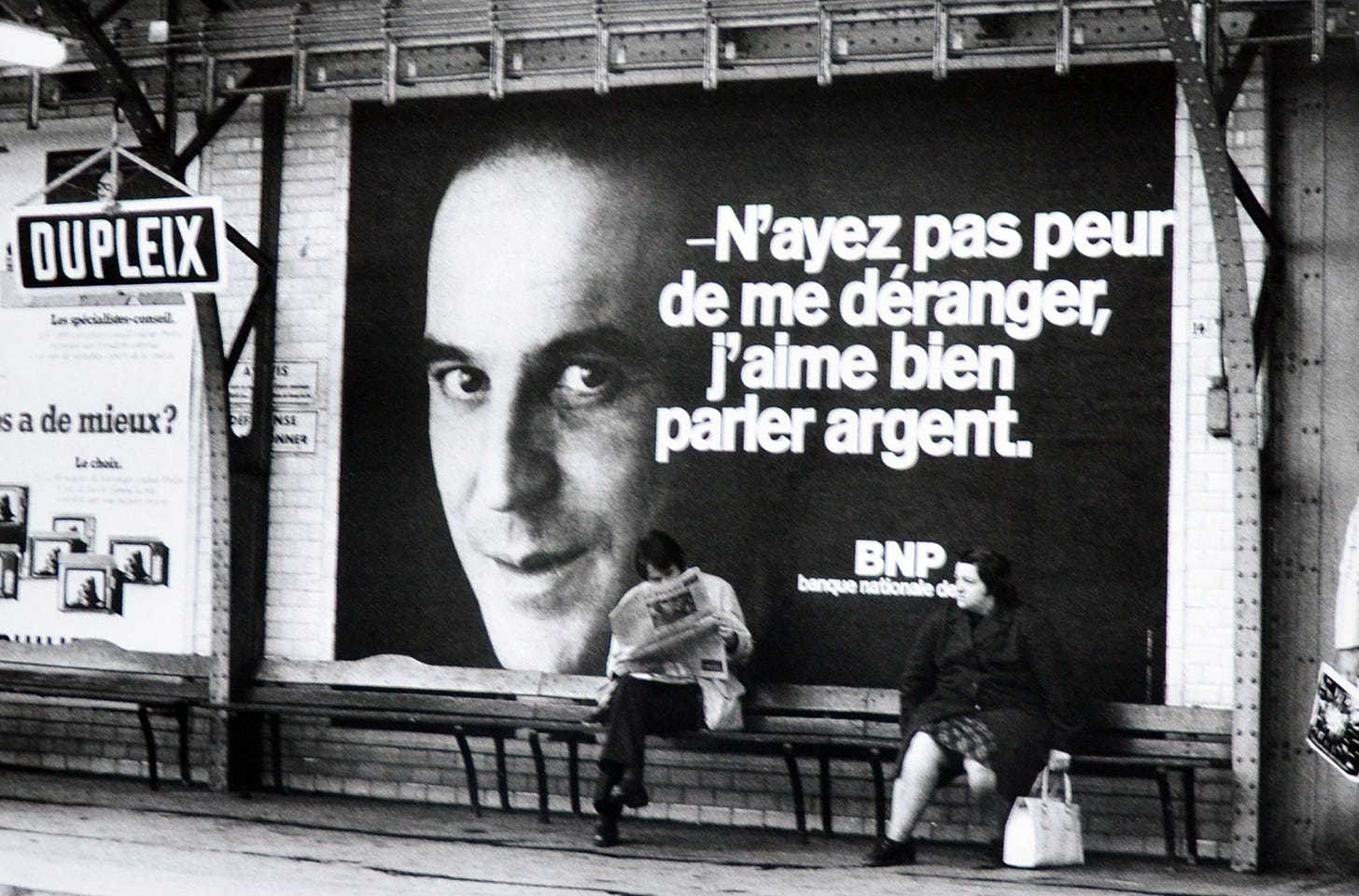

Doomscrolling – it really is both those things… more on this soon via Minecraft. First, Baudrillard, with two very deliberately chosen visual-public solicitations by capital.

~

“As an illustration of this, we might analyse an advert for the Banque Nationale de Paris (BNP), which reads: ‘I am interested in your money – fair’s fair – lend me your money and you may profit from my bank.’

To begin with, this is the first time (1973!) that capital (in its front line institution, namely international finance capital) has so clearly and openly stated the law of equivalence and, surprisingly, in the form of an advertising slogan. These things are usually unstated; commercial exchange is seen as immoral, and all publicity tries to cover this up as a matter of urgency. We may therefore be sure that this candour is a second-degree mask. Secondly, its apparent aim is to convince people on economic grounds to do themselves a good turn and take their money to the BNP. Its real strategy remains unofficial, however: to convince people by this ‘man to man’ capitalist openness, saying ‘let’s not be sentimental about this’, ‘no more of the ideology of dependence’, ‘cards on the table’, etc., and so to seduce people by means of the obscenity of revealing the hidden, immoral law of equivalence. This is a ‘macho’ complicity where men share the obscene truth of capital. Hence the smell of lechery about his advert, the salaciousness and smuttiness of the eyes glued to your money as if it were your genitals. The technique used by the advert is a perverse provocation which is much more subtle than the simplistic seduction of the smile (such as was the theme of the Société Générale’s [a bank – tr.] counter-offensive: ‘It is not the banker who should smile, but the client’). People are seduced by the obscenity of the economic, taken to the level of the perverse fascination that the very atrocity of capital exercises on them. From this perspective the slogan quite simply signifies: ‘I am interested in your arse – fair’s fair – lend me your buttocks and I’ll bugger you’, which is not to everyone’s distaste.

Behind the humanist morality of exchange there is a profound desire for capital, a vertiginous desire for the law of value; and this complicity, both economic and non-economic, is what the advert, perhaps without knowing it, seeks to recover, testifying to an intuition for politics.

Thirdly, the advertising executives could not have been unaware that this advert, with its vampiric image, scared the middle classes, so that to emphasise their lecherous complicity with this direct attack would provoke negative reactions. Why did they take this risk? Here we have the strangest trap: the advert was made to consolidate the resistance to the law of profit and equivalence so as to be better able to impose the equivalence of capital, profit, and the economic in general (the ‘fair’s fair’) at a time when this is no longer true, when capital has displaced its strategy and so is able to state its ‘law’ since it is no longer its truth. Announcing this law is nothing more than a supplementary mystification.

Capital no longer thrives on the rule of any economic law, which is why the law can be made into an advertising slogan, falling into the sphere of the sign and its manipulation. The economic is only the quantitative theatre of value. This, as well as the fact that the role of money in all this is only a pretext, is expressed by the advert in its own way.

Hence the commutability of the advert itself, which can operate at every level, for example:

− I am interested in your unconscious – fair’s fair – lend me your phantasies and you

may profit from my analysis;

− I am interested in your death – fair’s fair – take out a life insurance policy and I will

make your death into a fortune;

− I am interested in your productivity – fair’s fair – lend me your labour power and you

may profit from my capital;

and so on. This advert could serve as a ‘general equivalent’ for all real social relations.

Finally, if the advert’s basic message is not equivalence, a = a, fair’s fair (no-one is fooled, as the advertising executives well know), could it be surplus-value (the fact that the operation ends up, for the banker and for capital, showing the equation: a = a + a’)?The advert can barely conceal this truth, and everyone can sense it. Capital slips in and out of the shadows here, almost unmasking itself, but it is not serious since what the advert really says comes neither from the order of quantitative equivalence, nor from surplus-value, but from the order of the tautology:

not: a = a

nor: a = a + a’

but: A is A

That is: a bank is a bank, a banker is a banker, money is money, and you can have none of it. While pretending to state the economic law of equivalence, the advert actually states the tautological imperative1, the fundamental rule of domination. For whether a bank is a bank, or indeed whether a table is a table, or whether 2 + 2 = 4 (and not 5 as Dostoyevsky had it), is the real capitalist credence. When capital says ‘I am interested in your money’, it feigns profitability in order to secure credibility. This credibility comes from the economic order (creditability), while the credence attached to the tautology sums up in itself the identity of the capitalist order and comes from the symbolic order” (Baudrillard, 1976/2017, pp.68–69.)

I think here of Thatcher’s famous: ‘crime is crime is crime, it is not political, it is crime’.