Living Together, Somehow (the past six months)

distilling some key points from the past six months, part one of two

Here we are, heading toward the middle of the year already. Soon it will be winter; already the fog has set in and the sun is rising lower and later. Here I am, writing in the dark again, although it was only a month or so ago since daylight saving ended.

Since November last year, I’ve let Living Together, Somehow be taken in the direction of my spontaneous urge. If I have My Own Private Wotan here, then I’ve let the blog be about what Wotan wants.

Given the surge of words this has let out – a surge that surprises me perhaps as much as it tests your patience and stamina as a reader – I thought it might be timely to slow it down for a week, and, instead of keep pushing, take the pulse of what’s happened over summer and throughout autumn, and summarise very provisionally what ‘we’ might take from that, based on a summary of extrapolations.

In order to organise this, I’ve split it into months. For each post, where it’s relevant, I’ll let spontaneous intuition say what I now think was ‘in’ that post that is lighting up the neural networks this morning, then I’ll try to say what we might take from that, where we might go with it.

The purpose now is to continue to be intuitive, spontaneous and constructive, to make or build something illuminating (I know not yet what) from what has already been thought in words.

…and then, at 11.12am, I have hit 3,000 words again, and only got through half of it… …so I’ll follow up this Friday, or next week, with the remainder.

November 2022: the rentier neotopia of gain without labour: the pathological division of wages/ workload/ free time; the servile service economy of Deliveroo/Deliveree; the production of bull/shit jobs and precarity, and the on-time door ding dong delivery of monkey tennis and chimp shampoo

Late spring last year was the moment I realised a certain nascent direction. The pivot was into Gorz’ Critique of Economic Reason, which I’m continuing to read and use in the background. Here’s a shitty old PDF on the surface of the internet.

Sometime in the 70s or 80s, but clearly by 1988, the utopia of industrial modernity died.

In Australia, ‘we’ were too busy celebrating the bicentennary of colonisation1, without really realising – or did we – that we were celebrating a surreal punishment called penal transportation, and the expropriation of indigenous peoples from land and ways of life that have supported people 'here' for at least 65,000 years.

This utopia was comprised of ‘progress’, most of all the material-economic gains made through the application of science and technology to labour, with land appropriation, (mining, farming, and urban real estate speculation) as its 19C background. As Australia’s anthem sings it: ‘we’ve golden soil, and wealth for toil’.

Writing from Mitterand’s France2 Gorz’ view is that there was nothing left of this utopia by ’88.

Looking to ‘88 Bicentennial Australia – as an exemplar of culturally patterned Anglocapitalism under the sway of surging neoliberalisations in those decades – I disagreed: in this country at least, the utopia of ‘wealth for toil’ had been exchanged for one of ‘gain without labour’ (GWL).

As the neo-topia of the new aspirational rentier class, GWL was turbocharged by a historically anomalous total alignment of instituted politics, the banks, finance, news media, immigration, demographics, urbanisation, extraordinarily low interest rates (after 2008) and the inheritance of land-based wealth. GWL has endured to the present – but is now choking on its own contradictions and stupidity, and is beginning to expropriate a growing portion of its erstwhile beneficiaries.

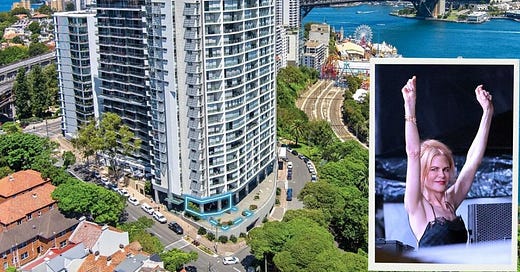

If we want an index of this, look at contemporary urban real estate; look at how Qantas CEO Alan Joyce’s second luxury house in Sydney3 and the fact Nicole Kidman just purchased her sixth apartment in the same a harbour-side luxury building (she lives in Nashville, FFS), while ordinary wages are now non-relational vis. most mortgages, and those who can’t afford mortgages are forced to compete to pay extortionate rents, often (it’s a dice roll, with little recourse) to morally indifferent landlords offering unsafe and unsanitary accommodation.

Looking back, we can connect the utopia of GWL directly to last week’s posts on fantasy, insofar as the idea of gaining without labouring neatly dovetails with the desires enacted by the compulsive online shopper (and bored, unskilled teen daughter) played by the Jenners, held together by fantasies of handheld control and consumer sovereignty (the queen with her wand who can compel delivery, if she has sufficient funds).

December 2022: the platform excrescences of the neotopia of GWL: pathological division of wages, workload and free time; the servile service economy of Deliveroo/ Deliveree; the production of bull/shit jobs and precarity, and the on-time door ding dong delivery of monkey tennis, chimp shampoo,

In December, I continued to elaborate what I would later (in February) begin to think about as involutions and excrescences: where it all breaks down, and where it all grotesquely en-warts.

Continuing to extrapolate from Gorz’, I suggested the tentative term Gorzworld as I explored very prescient descriptions of how the GWL society after the death of the utopia of progress produces a pathological division of work and free time: highly uneven distro of load and reward, and no free time for anyone. Burnout and red wine for the winners; burnout and cold rain for the precarious.

This dynamic raises the co-meaning of work and free time to a fundamental societal question:

what are we to do now, and what is the meaning of all these bull|shit jobs we’re doing?

In Gorzworld, a minority of the already enfranchised and privileged4 would end up working 60-80 hours a week doing ridiculously well-paid work. They do so with secure tenure over plush property (which they can afford to renovate and flip, and which has appreciated insanely in the past few decades). Absent a gambling, drug or phone sex addiction5, they would be accumulating (with the view of eventually reaching the threshold of GWL), but while having to ignore their kids (and farm them out to extracurricular activities, nannies, and gaming consoles) and partners and risk long-term health issues by suffering through a work-life balance so lacking it wants fixing and fixing through the continual and growing drilling and filling with niche services and delivered products – dildos and donuts, chimp shampoo and Deliveroo, delivered RIGHT NOW (back to last week's posts, once more).

I called this minority the Deliverees. The few of them I know seem stressed and lonely in their 2-3 million dollar family houses, as they crank through the 60-80 hour working week that nets them the 2-500k/year they ‘need’ to service their mortgages, holiday houses, holidays, renovations, and private schools. Perhaps they cry into their fine wine and bawl alone in their Teslas and XC90s; maybe they’re having a great time and are entirely content, and it’s only the ressentiment in my fantasy, and its cognitive biases, that ‘forces’ me to see them in this sad light (the muted sounds of crying in a plush car cabin). After all, this tack I’m taking was called ‘the politics of envy’ during the Howard Era, its king tide high tide in this country.

But to my mind, one of the notable psychosocial effects the stifling, strained eye, sore shoulders and neck overwork-affluence of the Deliveree eventually tends to create a character structure with very little imagination, poor theory of mind, a narrowness of experience and world view, and often a deep-seated fearfulness of the ‘world out there’. Covid didn’t make these traits any weaker, let’s say.

To the extent this becomes the case as the character pattern of that cohort, most Deliverees probably can’t articulate the societal sources of their trapped sadness Gorz is pointing to.

Or, if they do, they externalise, discharging the blame onto wrongful-causative Others. Maybe there’s an online community they can go on their phones, while they’re trying to shit, where they can take a dump on/with these bad Others.

Either this, or perhaps they pathologise their selves as deficient and chemically imbalanced6, get into wellness and positive thinking, or just get SSRIs and do ten sessions of CBT, so they can cope well enough to resume compulsively working to keep up with the Joneses, service their 30k/month household costs, and accumulate – reaching toward the utopian horizon, that glorious day when GWL will be reached (by which stage, they'll probably be able to afford the decade of complex, incapacitating ill health they'll endure, before they die7).

A growing, increasing number of people – perhaps the majority – have become the precarious service workers doing the shitter end of the bull|shit jobs (see my definitions) of the servile service economy compelled by the purchasing power of the Deliverees.

On the flip, given that many ordinary people’s wages now only just make rent, food and bills, and that even the formerly prosperous middle class professions will never achieve salaries and property capable of catapulting us into GWL, more of us, and eventually nearly all of us (and already many of us), now live in a world of labour and tasks compelled by banks, landlords, and employers, all of whom mediate the upward circulation of digital money paid to us and taken away from us8.

The beneficiaries of these groups, the Deliverees, live a disparate, incommensurable life, with a different class of conditions and expectations: people who don’t need to glance at their supermarket receipts and probably don’t need or care know what anything basic costs. People for whom a second cliff top house or a seventh apartment is just an investment that nets a return, not a cost that destroys savings and compels labour.

Thus: at the horizon of the neo-topia of GWL, we have a new class system, largely mediated by smartphones, effectuating a brutal social sorting mechanism that automates the production of inequality and precarity, and is driving gentrification, inflation, and wage-cost of living death spirals for the growing majority.

As we learned from the covid lockdowns, in Australia – in global relative terms an extraordinarily wealthy and privileged place9 – this system distributes 2-300 dollars an hour for non-essential work that can be conducted from home on a laptop, 21.38 an hour for the essential work that facilitates this. Despite the durable Anglo fantasy of meritocracy and hustle, this automated system provides almost no social mobility such that the ‘hustler’ Deliveroo will one day become the ‘hustlee’ Deliveree. Even if both groups worked 80 hours a week, at the end of 30 years, while the Deliveree might have cleared nine million in wages, the Deliveroo would only have made 2,667,60010 – there are now houses in the neighbourhood for sale for more than this11.

As Gorz might interject:

how can people integrate their lives in such conditions, how could they make meaning from it, and what could possibly be the meaning, or the point, of such a system?

February 2023: global systems, uncontrollability in a community of fate comprised of debounded systems; the surreality of the present’s involutions and excresences

Earlier this year my attention shifted slightly in a ‘global systems’ direction, especially toward spatial and temporal debounding, as well as involutions and excrescences. This held a lot of Gorz’ questions about work and meaning in abeyance – but only, I think, so I could (and can, and will) return to them with a clearer sense of the lie of the land, for having traversed it.

In looking back at Beck’s work on global risk society, what’s fundamentally at stake is how spatial and temporal debounding has produced a community of fate in with all of us – in groups, and as individuals – have to live together, somehow, yet (quoting myself) “with little in common: not quite Stiegler’s ‘panic’12, but not quite a good common or a functional community. This is among the things that globalisation actually means, as the lived effects of spatial debounding

A few other things slipped away in the wake there. First of all, Beck makes the important point that, in such a debounded community of fate, the fundamental role of governments is about feigning control over the uncontrollable. This actually aligns to some points I’ve raised about control and uncontrollability by way of Stiegler and Vogl, as well as (to a lesser extent) Rosa. Leaving aside (fantasies and techniques of) control and (the tragic irony of) emergent uncontrollability, it’s worth noticing the feigning. To the point: government now also fundamentally consists in dissembling and pretending...

they pretend they’ve got this, and we pretend we believe them.

This amounts to a dramaturgy and process no different from that explained concretely by Ian McKlellen in Extras.

So... they’re acting, and we lease out the space between our ears (McLuhan) and believe them (or not).

Fundamentally, if those in a position of office are pretending – so we can pretend we believe them – it’s because of temporal de-bounding. This was the second important point. Quoting myself,

“in such debounded scenes (so banal and so unevenly distributed), the future is also hurtling toward us all at once and all too quickly, and we have nothing but one another, nothing but our groups and institutions, however weakened and disintegrating, to carry us through. Who would not feel at least a little anxious and frightened in such a world?”

As with the points about the un|controllability of the world, some of what I’ve extrapolated from Beck can be put into a productive conversation with Rosa’s conception of social acceleration and his theory of modernity as metastability, the many Marxian accounts exploring metabolic rifts (Peter Frase brings them back in his Four Futures), and Latour’s gathering up of the anthropocene as a fundamentally different ‘age’ emerging since the postwar period.

Rosa and Latour had a crack at having this conversation: unfortunately, although it was fairly interesting, urbane and suggestive, I feel like Rosa got a bit defensive, then covered up his real disagreement by falsely overagreeing with Latour (about points where what they say is actually really different, and interestingly so), and they ended up not *quite* hitting it. For what it’s worth, I think Simon Michaux (see last week’s post) is doing a better job of mapping out the ‘break glass’ thinking we need now for the very bumpy transition which is very likely to happen sometime in the coming several years. It’s a shame Rosa’s work becomes so self referential; it’s a shame that Latour’s 2010s work, always hitting very important topics, doesn’t quite land (as well as his intellect makes it possible he could have), and that he passed away (RIP).

...but if we take these February concerns ‘back’ to the emergence of contemporary Australia since ‘88 for just a moment, well, if Michaux and others are correct: how will the servile service economy, still oriented around the utopia of GWL, how will its residents cope with a world in which – very suddenly, very quickly – everything which was smoothly containerised and arrived promptly in its little containers became scarce, unavailable? What happens when the Rube Goldberg Machine can no longer provide dopamine spurts on command? What does a society dependent on cheap fossil fuels, cheap clothing from K Mart, and the cheap delivery of take away food: what does it do when such things are no longer cheap, no longer available? We can only speculate, but the reality is surely a highly unevenly distributed ‘somewhere’ between Mad Max and A Paradise Built in Hell13. But like: what are Alan Joyce and Nicole Kidman gonna do? And what use would they be? Well, we might soon find out.

In the meantime, in February, as in the past three months, I’ve been trying to use text and selections from Google Images emphasise how weird the current moment is, how beset by psychotic juxtapositions we just scroll on by – as if it ain’t no thang.

I’m still not yet totally clear in exactly how and why involutions and excrescences will finally fit here as the theory is slowly building and clarifying. The terms emerged, and seemed to explain, but I’m still not in control of what or how. But I still sit with the intuition that we really have to think more about neijuan, and not just Other it a something only happening in China. Likewise, we have to move past this pernicious and self-serving idea that, somehow and in spite of everything, it’s still a meritocracy ‘here’, with a ledger that’s still operating. We still act like Peter Tosh’s first lines from ‘Get Up Stand Up’ (which I’ve been cogitating on since I was three years old):

most people think

great God will come from the sky

take away everything

and make everybody feel high

March: from glimpses of and glances at how the debounded way the world might be now to how and why we might cease to understand it, what that might mean in the face of AI hype

…TBC Friday…

which, at that time, still tried to somehow incorporate indigenous Australians into that celebration, as if they too should be celebrating it… or, at least, this is my cultural memory of it at the time. This injunction to celebrate is kind of repeated in the Sydney 2000 Opening Ceremony (and is placed there in the background in Peter Djiggir and Rolf de Heer’s Charlie’s Country). Mid to late 80s Australia, the Australia of INXS and Icehouse, was suddenly, weirdly very self confident, a stark contrast to the colonial self hatred and Tall Poppy Syndrome that had driven Germaine Greer, Clive James, Barry Humphries to London, and Robert Hughes to NYC.

after decades hanging with Sartre, the New Left, Italian Autonomists, post May ’68 Frenchies, the French labour movement, Marcuse and Illich (and even Fromm, once or twice)… Gianninazi’s biography is not the smoothest or most literary read, but it’s very scholarly and thorough… I hadn’t realised the extent to which Gorz was always ‘there’, like the protagonist in LCD Soundystem’s ‘Losing My Edge’.

There’s the six bedroom one in Mosman, and a five bedroom one in Palm Beach (same link). If you know Sydney geography as I do, this really gives me the shits. The properties are roughly 30km (a bit more than an hour’s drive) from one another, and in the latter case, it’s not even quite a ‘getaway’ or holiday house. It’s just another house, which, when you’re living in one, you can’t be in the other (and for a total of eleven bedrooms, when there’s only the two of you). At the very least, like Kidman’s choices, this lacks imagination, and isn’t even that ‘wow’ or interesting: just big and expensive and with harbour and/or ocean views. And the thing about Palm Beach is: you’re stuck on these windy little roads (that the council can’t afford to fix well), and you just end up at the supermarket in Avalon with the disgruntled old locals and new 1%ers… or cutting a hole in Barrenjoey and Pittwater Road. It’s not even a ‘helicopter to deep waterfront’ reality that you could get between, say, Torah and Portsea. Like all Sydney real estate, it’s poor value, and you’re stuck in traffic. And the thing is: Joyce has really not done a ‘bonus’ job at Qantas, if you read this account.

Interestingly Gorz’ work suggests correlations with Richard Reeves’ Dream Hoarders, info and commentary where it’s not the .01% or even 1%ers (of Occupy rhetoric) that have hogged it all so much as the upper middle class: obviously this is highly culturally patterned, but it’s interesting to me to see this American reality as roughly correlative with Australia in the grip of Gain without Labour. If I think of my institution, it is the substantial fact: although the excesses of the ‘CEO class’ (and above) are egregious (see Kidman and Joyce above), the big cost burden is made up of the many, many more people where I work who are between 50-70 years old and pulling down between 2-500k/year… upper middle management &c….

Yes, alcohol, but you can afford it in this bracket… and phone sex is really expensive, Australia cocaine expensive.

And this genders hard… it’s just an anecdotal impression, but it seems that those who gender themselves as men here tend to blame others, the women themselves.

And wow: can you imagine what it would feel like to ‘lose everything’ if you invested everything in accumulating and having, and avoided the very thought of death, let alone the death of the self and the ego? Holy fuck, that’s some samsara.

Even this process is now incredibly abstract: how much of our money do we ‘see’ or ‘feel’? Consider by way of illustrative contrast Tomi Ungerer’s Three Robbers, or Big E’s ‘Gimme the Loot’.

Like, if ‘we’ still have the utopia of GWL, it’s also because we have like a million extremely rich people here, or whatever… likewise in the US and England and Japan….

and can you actually imagine working deliveries 80 hours a week for thirty years?!

In fact, that’s what a renovated four bedroom house, a ‘nice family house’ now costs in my gentrified ‘hood.

In his usual misrerabilist way, Stiegler talks directly of how there is no longer a ‘we’, just an anomic mass of disaffected individuals panicking: the immediate context was the disorder in France’s banlieus in 2005, but as always, there’s the rhetorical marrying of the ‘worst’ with the idea that, willy nilly, everything is headed to these skids totally/badly/now. It’s a shame Stiegler exaggerates so much and tends to use obsolete, parochial examples (this is how they read from here/now), because, as often, I think he’s onto something, his intuition serves him well. An always interesting thinker who often wrote shit, hasty books.

This also lines up with Carolyn Nordstrom’s idea of global shadows: people co-operate to get their needs met. In the *absence* of a Hobbesian sovereign (external, visible, authority imposing), there *is* trust (it’s the opposite of what Hobbes says, based on what she saw in Angola and elsewhere… not that it’s neat or pretty, just that it *does* meet people’s needs, and people are really creative, they learn, and they trust – selectively).