Unboxing the amateur unboxer

opening the boxes of consumption we live in, noticing the plague of objects that's burying us

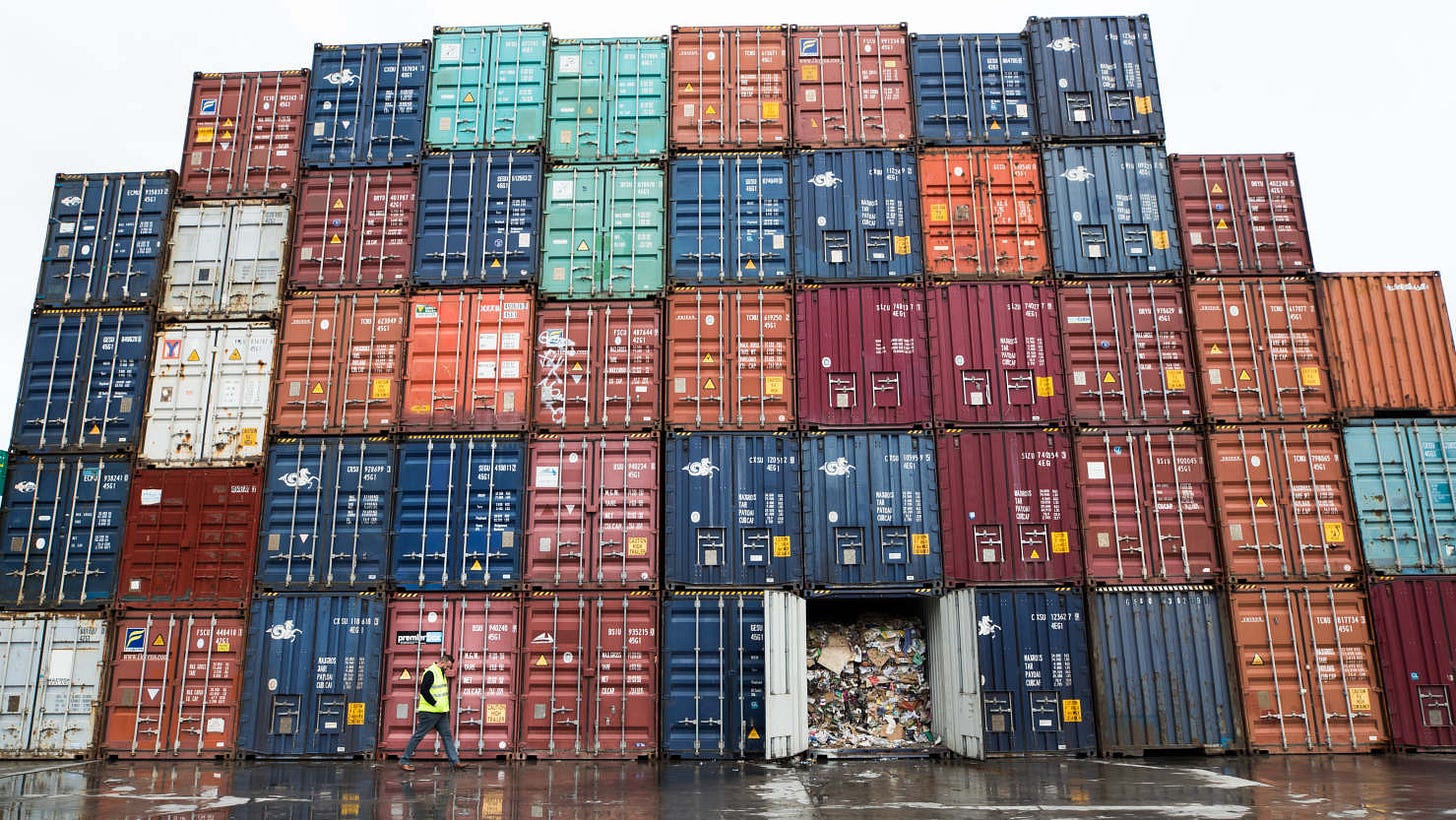

At what point did we become the species whose most popular category of YouTube video is unboxing? Future historians might note this as the precise moment when we became consumed by consumption. For we are, above all, a community of fate trapped in a global risk society whose spatial and temporal deboundings, as I’ve discussed, are packed into boxes, wrapped with sticky tape, and sent, containerised, around the world.

Containerisation is always about decontainment; the conveyance of the object and its unwrapping is plumped by the packing foam of our desires. And desire, as I began exploring alongside fantasy, is no coincidence.

In the nineteenth century, consumption meant a hacking cough, a seasonal epidemic, a sickness unto death. In the twentieth century, as the circulation of soap and fresh air coursed through better ventilated rooms and proper sewerage, this fate and meaning was gradually replaced by our fate and meaning. It’s curious to note: by Google N gram’s estimation, consumption – in discourse – increased dramatically in the 1970s, peaking between 1978-1980. Strangely, in the Anglophone world at least, talk of consumption has been on the slide since. From the same moment in the late 70s, however, unboxing has bounced like a crazy ball into word-formed consciousness, hitting its first peak in 2007, sliding slightly by 2014, before bouncing into the political present.

What was being noticed in the 70s, and so acutely by ‘78; what is passing into less notice, or passing unnoticed, in a world gripped by the desire to watch unboxing videos? What does it mean to want to watch a stranger’s hands take a commodity out of its box? Who’s the fluffer here, what is the money shot? Who or what is grasped and held, and what is the unboxer holding hands with? And what is the fate of the unboxed object; whither the box?

Early last year, I posted about one of the collective fates of a society of unboxing: the plague of objects we live with/in, that we leave to our relatives after death as our afterlife, and that for so many people of the global middle class becomes the emotionally and physically draining chore, the consuming task through which our loved ones sift through whatever it was that our lives amounted to by the time we left our stuff stuffed houses for the hospital where we passed into eternity, by way of a cloud of opioids and invasive palliative measures. Alongside what we shit and eat, in quantitative terms, our houses are the repositories of the ‘greatest thing(s)’ we will ever have produced. We leave our houses full of objects as parting gifts to those we say we love most. Like Viking kings and Pharoahs, we are buried among our many things; unlike them, we are buried by them, not in battle and without glory – then we are incinerated, so that our bodies do not take up too much space, as the buried would. Across the span of our lives, we know we are enacting these accretions and what that means, cumulatively; yet by the time this meaning has accumulated to become fate, by the time it has ‘happened’ (all too late) and come due, we are surprised by what we ‘knew’. Then our sons and daughters are left alongside the arrangements to hire the skip and – mostly – transform the precious things of our lives into the landfill and op shop junk that 90% of it in fact always was. We are a culture that transforms into bric-a-brac, landfill, and microplastics, across our unboxing lifespan.

Jean Baudrillard’s Consumer Society: Myths and Structures, is still one of the best things of his I’ve consumed, still fresh out of the box, fifty-three years after its publication. In the coming weeks, I’m intending a few posts where I explore some of its key points of resonance for me – and hopefully for us – living together, somehow, in the 2020s, this interregnum, this ?micro? era of unboxing. Baudrillard, extrapolating critically from Galbraith’s Affluent Society by way of looking at postwar US from post May ‘68 Paris, wishes to disabuse us of our naivety. Consumption is not and never was about utility and ‘happiness’ achieved via the felicific calculus, in the way we read back the Benthamite schema as the mythology of Anglocapitalist economics. Consumption is about

profusion, successions, sets of objects;

their setting in motion as mana that falls to us from heaven as magic and miracle; and

our collective expenditure through the wilful, ecstatic, wanton hyperproduction of excess and waste.

I’m intending to give each of these genie’s bottles a rub across August, but to come back to the unboxing we started with: at what point did we become a society that watches strangers remove commodities we have not yet ordered or touched from their boxes, and what might that mean? I’ll return to point back to what the Jenners have said to me about this, but first, let’s open this box by focusing on the plague of objects, with Baudrillard’s opening paragraph:

“There is all around us today a kind of fantastic conspicuousness of consumption and abundance, constituted by the multiplication of objects, services and material goods, and this represents something of a fundamental mutation in the ecology of the human species. Strictly speaking, the humans of the age of affluence are surrounded not so much by other human beings, as they were in all previous ages, but by objects. Their daily dealings are now not so much with their fellow men, but rather – on a rising statistical curve – with the reception and manipulation of goods and messages. This runs from the very complex organization of the household, with its dozens of technical slaves, to street furniture and the whole material machinery of communication; from professional activities to the permanent spectacle of the celebration of the object in advertising and the hundreds of daily messages from the mass media; from the minor proliferation of vaguely obsessional gadgetry to the symbolic psychodramas fuelled by the nocturnal objects which come to haunt us even in our dreams. The two concepts 'environment' and 'ambience' have doubtless only enjoyed such a vogue since we have come to live not so much alongside other human beings – in their physical presence and the presence of their speech – as beneath the mute gaze of mesmerizing, obedient objects which endlessly repeat the same refrain: that of our dumbfounded power, our virtual affluence, our absence one from another. Just as the wolf-child became a wolf by living among wolves, so we too are slowly becoming functional. We live by object time: by this I mean that we live at the pace of objects, live to the rhythm of their ceaseless succession. Today, it is we who watch them as they are born, grow to maturity and die, whereas in all previous civilizations it was timeless objects, instruments or monuments which outlived the generations of human beings” (25, emphasis in original).

To begin here, there is a simple truth in what Baudrillard was noticing by 1970: look around you now. You are probably in a room. This is already unusual in the balance of our species history. We have come to be a species that lives in boxes and puts boxes in these boxes. And then: how many people are in this room you are in (or, if you are outside, are you holding the box of your phone in your hand)? As I sit and write, I look to my right: boxes and boxes of my records, most from the early 2000s. To my left, the bag I carry to work, and in it, the ‘box’ I put my laptop in, alongside my headphones and raincoat – leaving enough time for the box of Lego characters I picked up for my son yesterday. In front of this, by the door, a mop bucket I’ve filled with ‘recycling’, mostly empty boxes and cans, because our inside recycling bins overflow – with boxes – if we don’t diligently stay on top of our household’s wasting process. In the garage (a box), in the family car (a box), in the boot (a box) there are two boxes full of stuff, most of it books and objects we’ve foraged from op shops, which we are returning to op shops. Out the front of any op shop, and especially after the short Christmas break (which, if nothing else, is an orgy of unboxing, followed by the ill feeling indigestion of processing and evacuating what we’ve consumed), the neighbourhood op shops of this global city of the rich world are heaving and stuffed with dumped boxes of stuff, in defiance of the CCTV cameras and polite or passive aggressive signs asking people to please not leave boxes of stuff out front of the op shop outside of business hours.

As a “fundamental mutation in the ecology of the species”, this world of boxes we inhabit – and that inhabits us – we should also notice the extent to which this contrasts with the many other ways in which we have lived together. What would indigenous Australians three hundred years ago, surrounded as people were by one another and country, and a more constrained set of very useful and pragmatic tools we knew intimately and made ourselves, or that were made for us by someone we knew – make of this mode of existence we have ‘chosen’, and that buries us? What would my coloniser-ancestors from this ‘same’ city of the 1880s have made of a tram (which they would have recognised) filled with passengers staring into flattish black boxes emitting strange blue light, and moving images of human hands roving over boxes?

My ‘environment and its ambience’: it’s a little cold now, but as I exist in a thermostatically controllable ‘environment’ (a box with a feedback-aware circuit ‘in’ it), I can tint the temperature ... if this posting’s soundtrack Dorisberg and Mullaert’s That Who Remembers gets too loud for my box, I have another feedback circuit by way of the volume knob on my amplifier: I can turn them down, tune them out, turn them off, send them back to Malmö, switch to another ambience, which will emerge from the black boxes of amp and DAC and speakers. The strangeness1 of this banality, that we also live inside Pandora’s box, and are usually not curious about the oddness of this preferred situation of existence.

The ‘pace of these objects’ outstrips us, too, it is part and parcel of logistics and bin night and the social fact of acceleration that Rosa notices as the life that lives us (with barely enough time to do so, always rushing, full on, full time). Yesterday I had to make it to Brickville (‘the home of bricks’, all in boxes, and all boxes or like boxes) before my son’s box of bricks became unavailable for a day. Last night was bin night, and even one fortnight’s missed ‘recycling’ means a full week or two of strategising, of taking green bags to other people’s yellow bins, getting ride of the wasted excess we ‘believe’ is being turned back into things we can overconsume ‘sustainably’.

This burial we slowly inflict on ourselves and one another, decades prior to our own death, is the accretion of a strange belief that we can keep going on like this, and that doing so is ‘growth’ and prosperity. The strangeness of this ritual, in light of the evidence we also know, is worth noticing a little more. So much pastoral care for so many lifeless objects; so many humans as obstacles between us and our getting the objects we love more than them.

Back in May, I looked at how our fantasies are no coincidence, and I zoomed in on the debility of the konsumption of Kendall Jenner, reperforming2 her inability to kut a kukumber. In that post, I concluded as follows – but revisiting it through Baudrillard’s opening paragraph helps us unbox it again without feeling like we’ve been delivered something we’re already bored of owning and are ready to waste:

“In the final analysis, what’s interesting here is how the fantasy of control (and its wand) and the fantasy of the sovereign consumer (on her throne, in her kitchen) is overdetermined by ‘whatever’: global capitalism, for now, for its upper middle and up, can compel labour to bring almost any object to our door through the Rube Goldberg machine. In the background, Depeche Mode’s ‘I Just Can’t Get Enough’ plays; it’s playful, it’s funny – how stupid it all is.

But to push this a little further: is the fantasy now not the push beyond erotic fantasy back into libidinal indifference? No one is really getting off here, no one is getting filled… there’s just landfill after ding dong. And moreover, is this not also an ad that demands preparedness of the supply chain on behalf of a set of consumers who are so so disorganised, unprepared, and helpless?

Uber Eats is now here to service the unpreppers, in a sense”.

There’s something more – and more interesting, and more textured, and that tells us more richly who we are or what we’ve becomer – ‘in’ the whatever, something of our debility and dependency, something that happened to us as we embarked on this mutation in the ecology of the species that has ‘arrived’ with the delivery of the unboxing video and the amateur unboxers we in fact mostly are. In the coming weeks and posts, I’ll try to get Baudrillard – dead in a box though he is – to help us think through it.

William Gibson is very attentive to this: that with recorded music, for the first time in history, we can hear the voices of the distant and the dead.